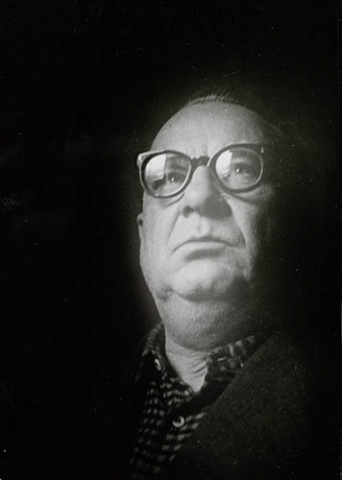

For Baumeister - as for many artists - the 'Stunde Null' (zero hour) was a longed-for new beginning. His productivity had not suffered a real break during the years between 1933 and 1945, but now art production could take place in public again. Even if the Stuttgart studio was destroyed and plundered and the residence could only be reestablished with difficulty: in October 1945 Baumeister exhibited for the first time again in Germany with other colleagues in Überlingen. And all at once he was at the center of art life in Germany.

Exhibitions in the Postwar Period

The artistic significance that the public recognized in Baumeister is revealed by the many exhibitions and participations in these years that consistently received great acknowledgment.

Among the most important are the survey show "Modern German Art since 1933" in the Bern Kunsthalle in summer 1947, solo exhibitions in Munich, Brunswick, and Stuttgart, an international exhibition of abstract painting in the Paris 'Salon des Réalités Nouvelles' in 1948, and in the same year the first Biennale in Venice after 1945. In summer 1949 the American military government in Munich organized the first comprehensive exhibition of German postwar contemporary art under the title 'Art Production in Germany' and at the end of 1949 Baumeister traveled to Paris for the opening of his exhibition at the gallery Jeanne Bucher, where he had already exhibited before and during the war. Moreover, important European museums expanded their collections with works by Willi Baumeister.

Appointment to the Academy of Art

Already a few weeks after the war's end, Willi Baumeister was under consideration as either director or teacher at the Stuttgart Academy. After he turned down an offer from Dresden in February 1946, he accepted the professorship and his own painting class in his hometown in March 1946. In 1951 he became the academy's deputy director and retired in February 1955.

Production pushed to the Limit

His reputation in Europe grew steadily. In Paris in 1948 he was called "Le Picasso Allemand" (the German Picasso). At the end of 1949 his friend Fernand Léger wrote: "in my eyes Baumeister occupies an extremely important position among modern German artists".

Baumeister exhibited, wrote numerous articles, taught, and participated in art juries; not least of all he painted incessantly and since 1945 had been at the easel almost daily. Thus it was hardly surprising that the restless activity between exhibitions, academy, and studio would force him to retreat to a health spa in Bad Ditzenbach in 1949.

The Unknown in Art

In fall of 1947 the first edition of his book, "The Unknown in Art", was published. In this book, which counts among the classical artist theories of the modern age and which Baumeister began writing during the last war years, he comments on artistic production and on the role of the viewer. He also presents an overview of the history of abstract art. It is Baumeister' early contribution to the understanding of modern - abstract - art that he subsequently and vehemently defended from all attempts to pit it against representantional art, as exemplified by the Darmstädter Gespräche (Darmstadt Dialogues) beginning in 1950.

Theater

Two years after the end of the war Baumeister took up a former activity and, after a long interruption produced stage designs and costumes again. The ballet "Liebeszauber" (Spell-bound Love) in Stuttgart in 1947 became as much of a success as the play "Monte Cassino" in Essen in 1949. Further designs followed until 1953. As such Baumeister returned to his earlier theme of applied art.

New Techniques

Willi Baumeister never wanted to come to a standstill; his paintings reveals - technically and formally - his constant pleasure in trying out new things. When silkscreen printing techniques became known after World War II, he had the idea to use and develop it further - in the form of the serigraph - for artistic purposes. He carried out his first works together with Stuttgart printer Luitpold Domberger. For Baumeister, Serigraphy ranked equally with other original graphic techniques such as etching and lithography, which he now often used, too. Between 1946 and 1955 he produced around 90 lithographic prints and some sixty serigraphs. He often translated a painting into the language of the graphic print and varied it in the process. During the last years of his life up to 1955 Baumeister designed numerous posters in silkscreen and thereby also forged a bridge to his beginnings as a sought-after typographer in the 1920s.