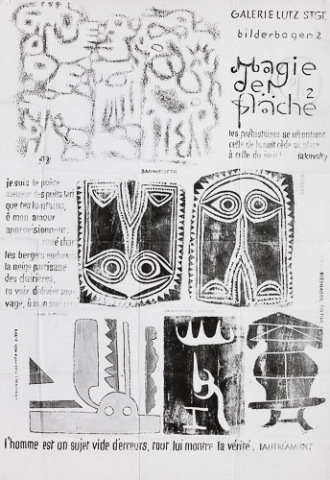

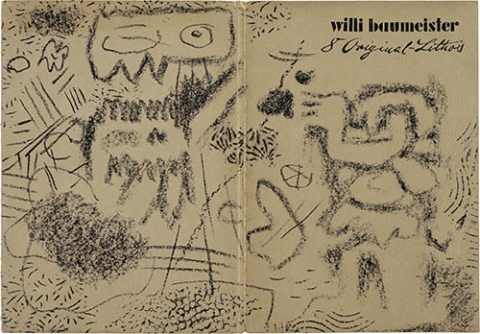

Between 1919 and 1943 lithography (along with the related offset printing) was the only original graphic printing method that Willi Baumeister used. By 1955 he had produced a total of 150 leaves that, in addition to the paintings, contribute important accents to the corresponding work phase.

Since at least in the initial years he achieved little definite character by chance in his works, he largely rejected the woodblock and linocut techniques as well as etching.

Clear and Consolidated: The Early Works

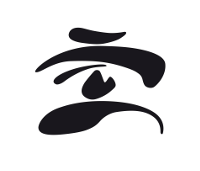

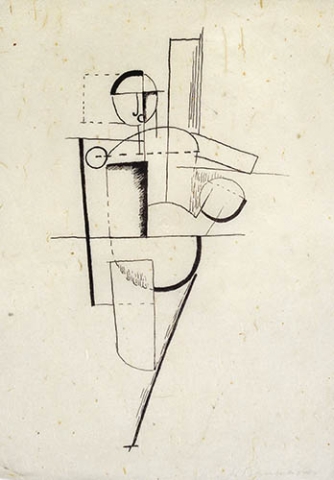

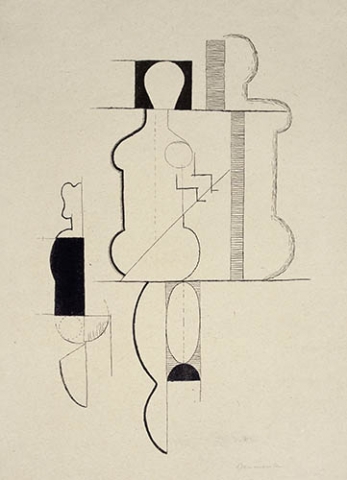

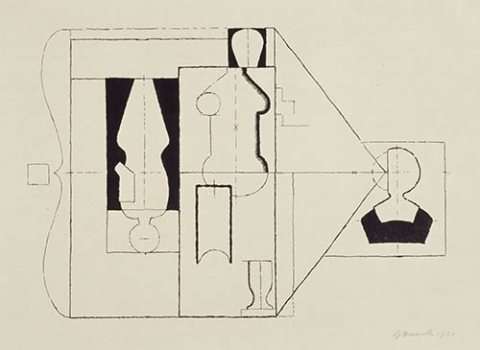

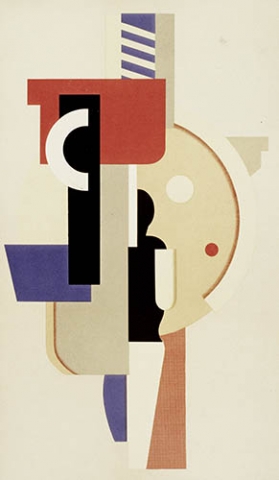

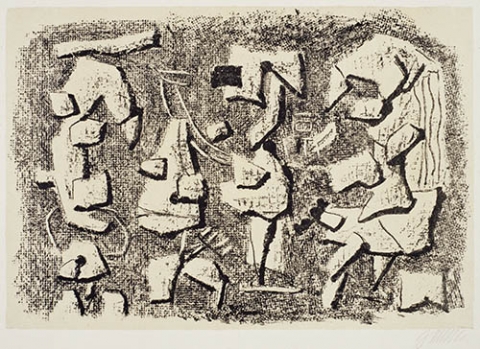

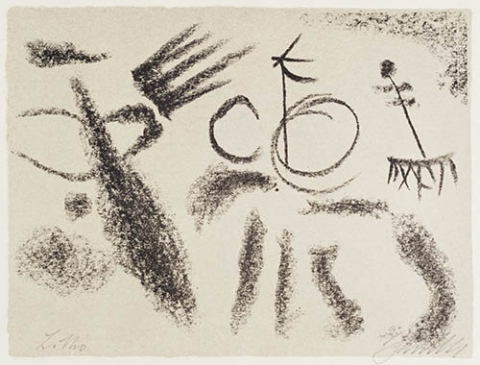

He endowed the earliest lithographic leaves of 1919 to 1922 with the tersest of pictorial means ( e.g. Figure, 1920 - Apollo, 1922). For him, strokes and shading entirely in black on toned paper were the appropriate forms of expression for the desired abstraction of the human figure and structuring of the picture surface.

He translated the characteristic materiality that preoccupied him in the Wall Pictures during these years into the lithograph, using shading, scored and blackened surfaces, and thin and amplified outlines. This resulted - even more so than in the drawings - in clear, formally extremely consolidated compositions.

The earliest preserved chromolithography, Figure and Circular Segment, dates from 1925 and remained the only one until 1936.

More Flowing Forms and Stronger Abstraction

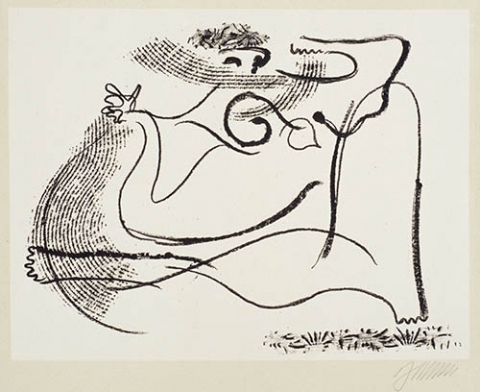

Only a few lithographs are preserved from the Frankfurt period period between 1928 and 1933 ( e.g. Athletes at Rest, 1928).

We know from the drawings that Baumeister destroyed numerous of his athlete renderings because they later appeared too naturalistic to him. We might presume the same here, too, although it was no doubt chiefly a lack of time that kept him from making lithographs. He increasingly turned to the technique again around 1934, after losing his teaching position.

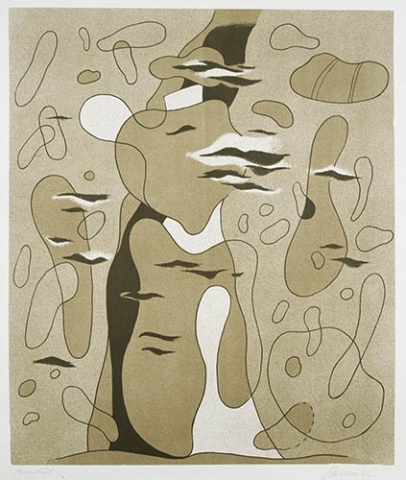

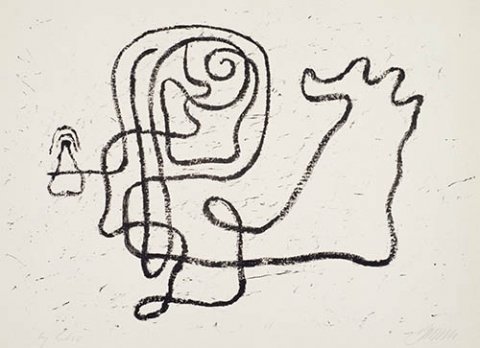

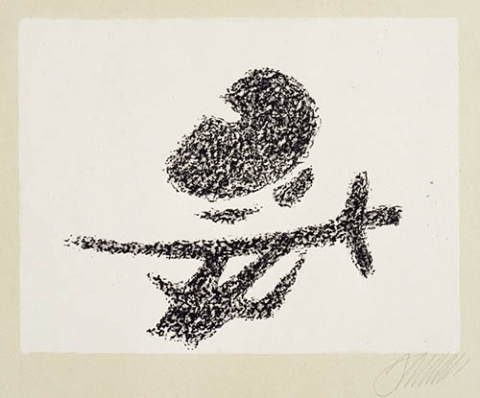

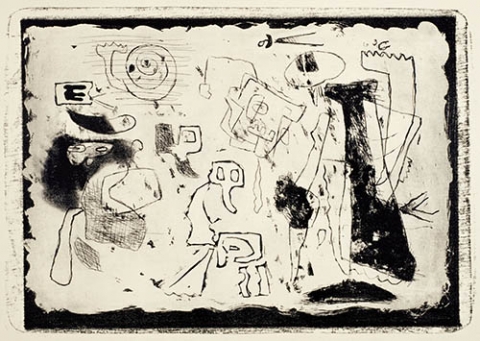

In contrast to the geometricized figures of the 1920s, he was now interested in movement, without losing the extreme reduction of the drawing. Between 1934 and 1937, the intensified use of graduated tonal values, an even clearer surface emphasis (Tennis Players, 1935 - Painter, 1935/36) and a drawn quality bordering on the nonrepresentational ( Line Figure, 1937) characterized the graphic works.

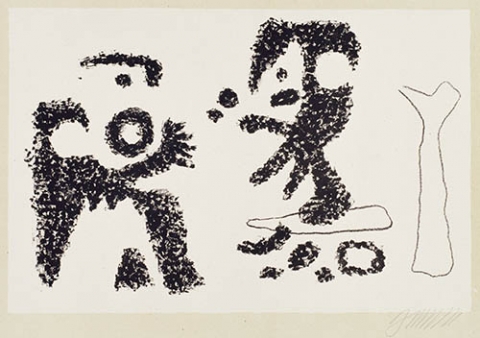

Marking the end of this phase are a few Line Figures and compositions that Baumeister called Formlings and whose kinship with the Ideograms in the paintings is apparent.

Painting Prohibition

In the years after the Munich Degenerate Art, in which pictures by him were also shown, and after he was imposed with a ban on painting and exhibiting, Baumeister produced further lithographs. Alongside the lack of materials, the circulation of graphic works would have meant an additional danger.

After World War II

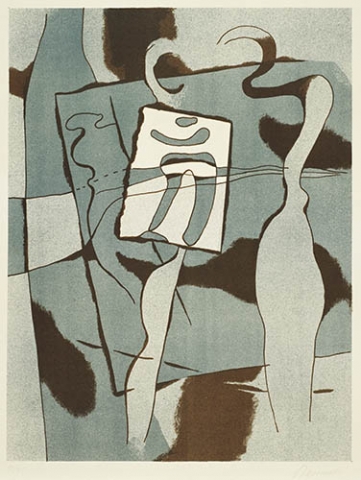

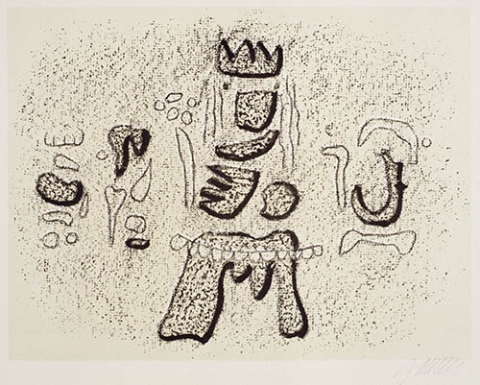

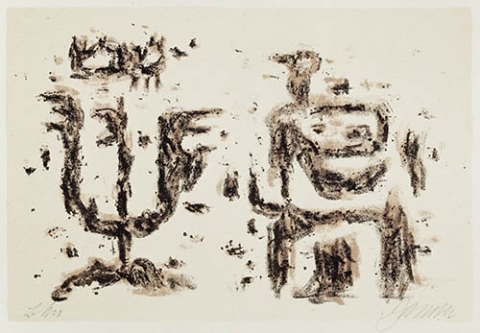

In 1946 Baumeister produced the 12-lithograph portfolio Salome and the Prophet in which he published a few of the 1943 Biblical illustration series drawings. He certainly retained the motifs from the wartime sketches, although formally he worked out even clearer compositions and figurations that, in regard to a circulation of the portfolios, was also understandable and sensible.

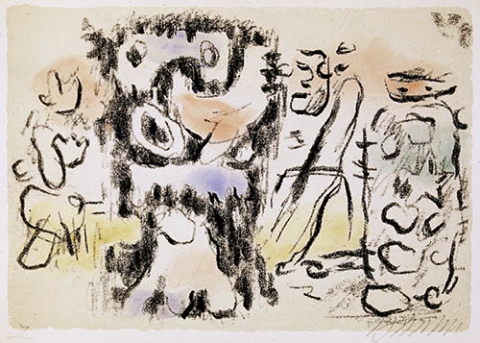

In two other portfolios of 1946 and 1947, he likewise took motifs from previous years' drawings, including scenes from Africa, Figure Walls, and other abstract, chiefly figural renderings.

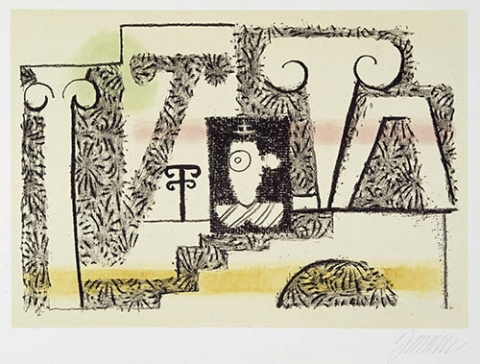

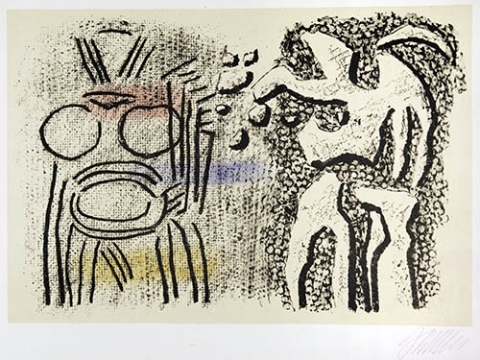

Primary colors as well as green now emerged in some leaves again in the form of watercolored Islands that concurrently appeared in many paintings and silkscreen prints (e.g. Primordial Forms, 1947). But even without the use of color, Baumeister realized works with highly nuanced tonal values by using blurring, chalk structures, and the frottage technique.

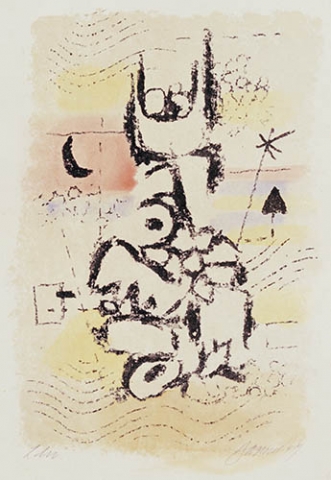

The Engagement with Surface and Color

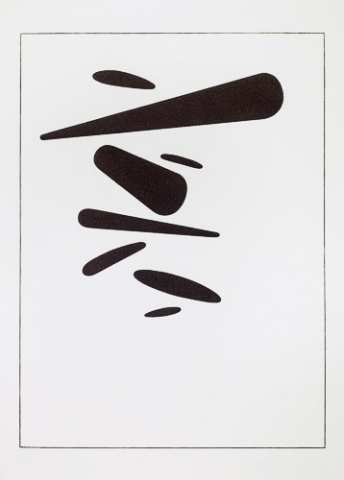

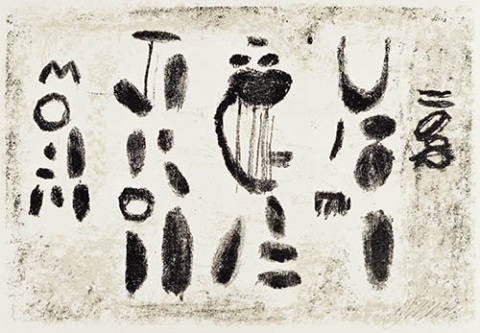

In the last years Baumeister turned more strongly to the serigraph which offered him a much broader opportunity to produce color graphic works. By contrast, he largely avoided intense coloration in the lithographs and increasingly worked with light tonal plates and a grainy lithography stone to reduce contrasts.

The leaves Crucifixion (1952) and Safer (1953) most closely correspond to the artist's intention. At that time he could also make the desired relief structures in lithograph with the means mentioned above. Now it was even possible for him to translate the use of sand in his paintings into the language of the graphic print.

The monumental Crucifixion represents a climax in Baumeister's lithographs. It is the largest graphic print of all and of great suggestive power. Here the print is in no way inferior to the corresponding painting of the same year.

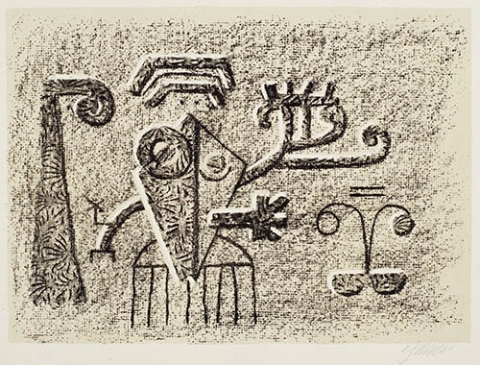

Pleasure in Experimenting

In the last lithographs dealing with the Aru and Han-i themes, which Baumeister only made into an edition as an exception, he experimented with cutout stencils. This again reveals that he constantly searched for new ways to realize his artistic intentions. In the two Stuttgart printers, Erich Mönch and Luitpold Domberger, he had also found two congenial partners.