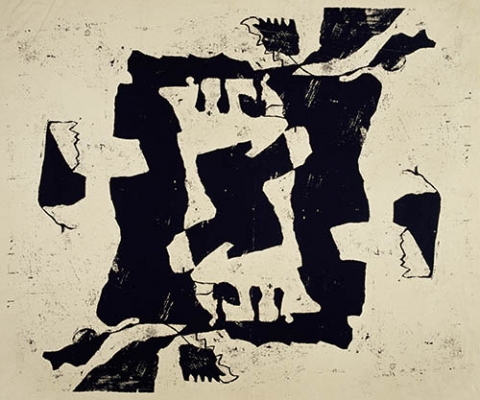

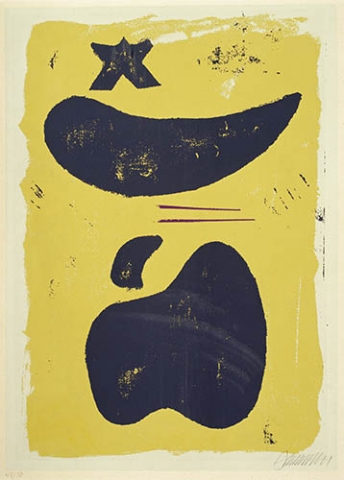

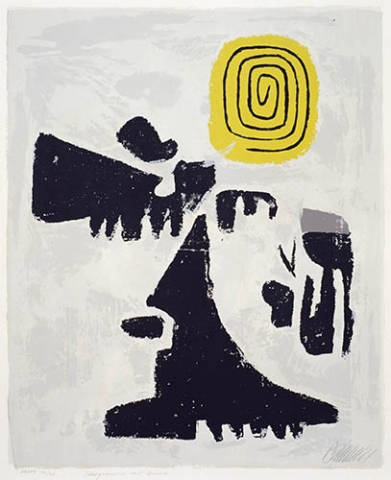

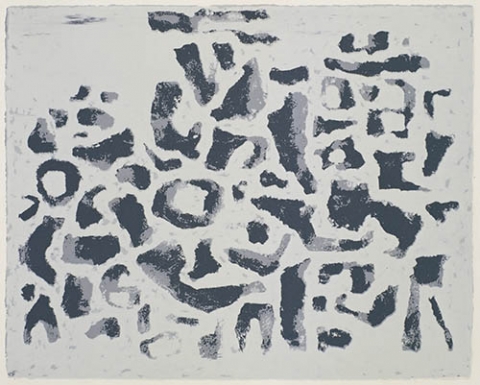

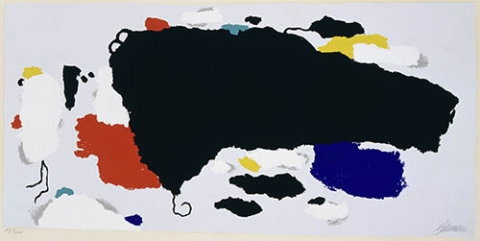

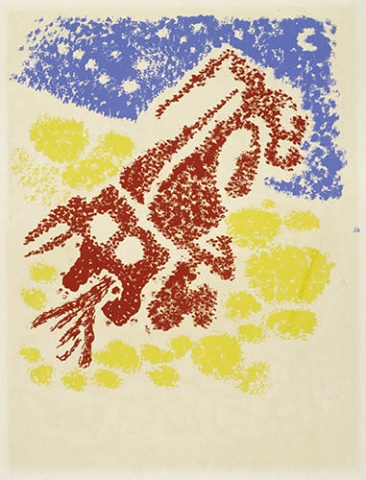

Through exhibitions at the America Houses the silkscreen print technique became known in Germany after World War II. Willi Baumeister first visited one such exhibition in 1948 and recognized that some of his artistic intentions would be optimally realized by this means, particularly the use of color and printing without manual traces. With it, multiple colors - even white and black - could also be printed overlapping one another.

In addition to the artistic aspects, the artist was also aware that by purchasing a serigraph print those with slimmer wallets could also acquire a real Baumeister.

In 1952 Willi Baumeister wrote in a Neue Zeitung article:

Fundamental to the procedure is that the taut screen is made partially impermeable, while the permeable parts allow the color to pass onto the paper. The partial blanking out can occur through glue or glued-on paper.

Interestingly, Baumeister also worked with stencils in his lithographs of this period. His pleasure in experimenting can be seen across all media and techniques.

Art Instead of Reproduction

In the same article Baumeister also stated from the outset that the silk-screen print was an artistic technique, not mass-production:

In the artistic sense, screen prints correspond to the original graphic procedures (litho and etching) with which the artist produces a negative. Since we are now dealing with hand printing, the editions for posters are limited to around two thousand.

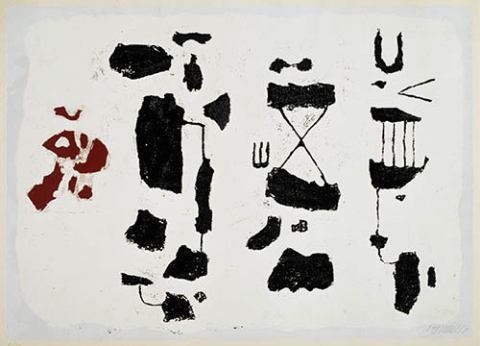

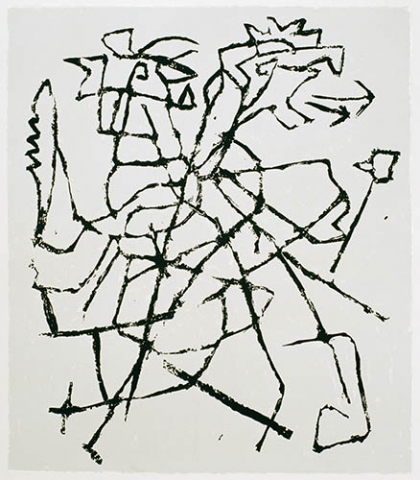

Willi Baumeister exclusively used the new medium manually and transferred drawing and paint onto the carrier himself. Concentrated handwork was necessary when he applied multiple colors - in so far as they did not overlap - onto the screen simultaneously.

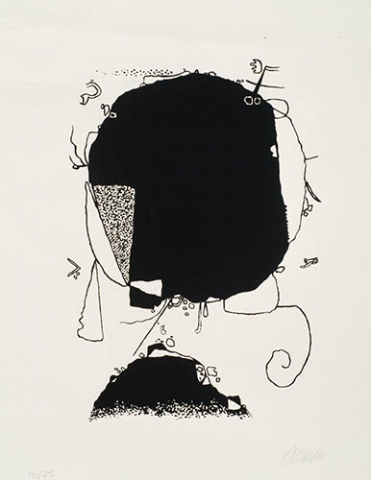

In many respects, Baumeister's silkscreen prints thus concerned the original graphic work in the narrower sense, because the artist himself prepared the print media, oversaw the strictly limited edition, and finally, signed and numbered the leaves meant for sale.

Artist and Hand Worker

Furthermore, an outstanding cooperation with the printer was essential. Baumeister found this in 1950 in Luitpold (Poldi) Domberger, who coincidentally had set up his workshop in the same ruin that housed Baumeister's studio. Already in 1952 they exhibited the fruits of their collaborative work in the Hacker Gallery in New York.

For Willi Baumeister, the handcrafted always held - as we know from the origins of the first wall pictures and earliest typographical works - a great deal of importance. In his book The Unknown in Art, he wrote in 1947 that in the wake of the new evaluation of line and plane, the elementary-handcrafted underwent a renaissance within "high" art.

An Important Medium in Baumeister's Production

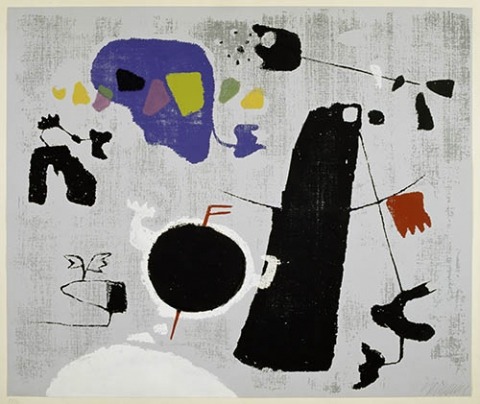

Following the first eight leaves produced in 1950, the number of silkscreen prints in Baumeister's oeuvre steadily increased. Prior to his death in August, he produced 18 in 1955 alone. At the same time, their total number noticeably exceeded that of the lithographs. This reveals that Baumeister's intentions were chiefly realizable with the silkscreen print.

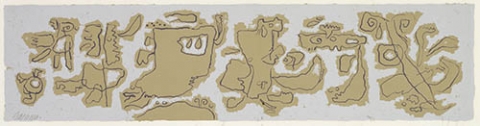

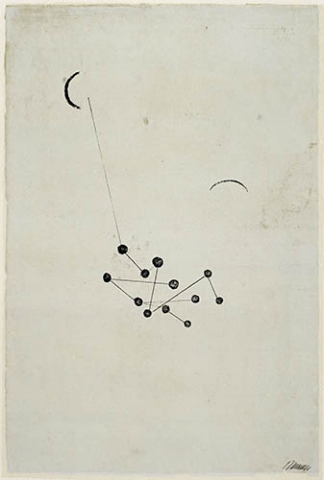

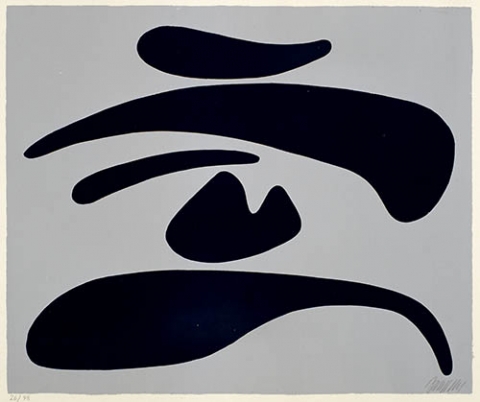

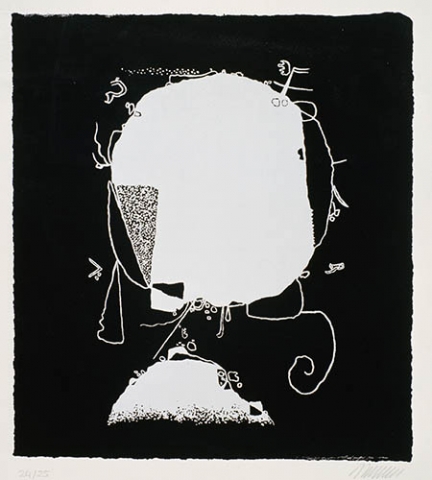

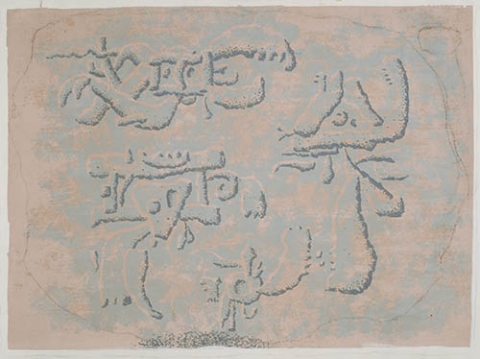

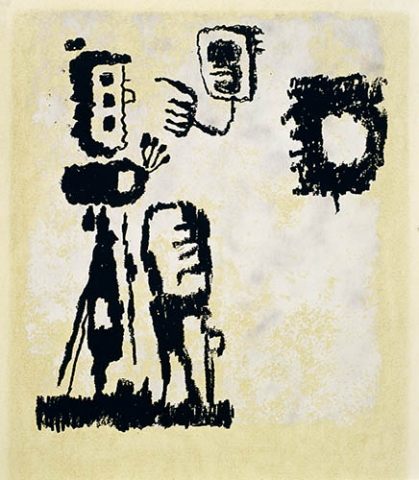

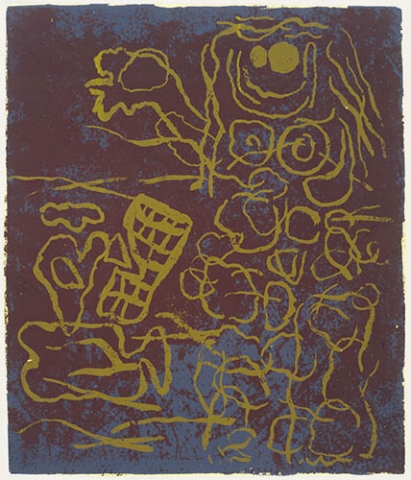

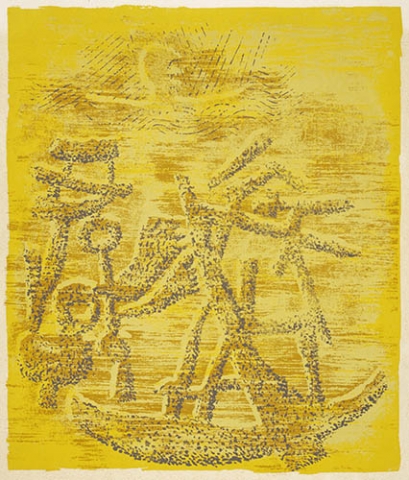

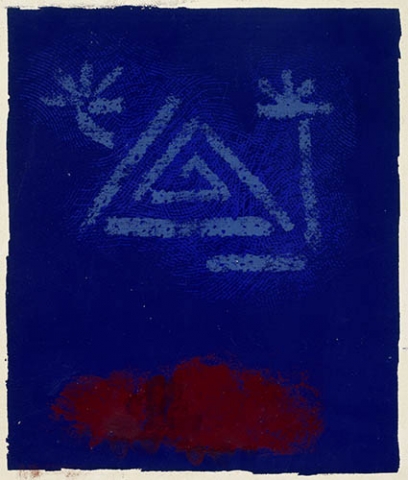

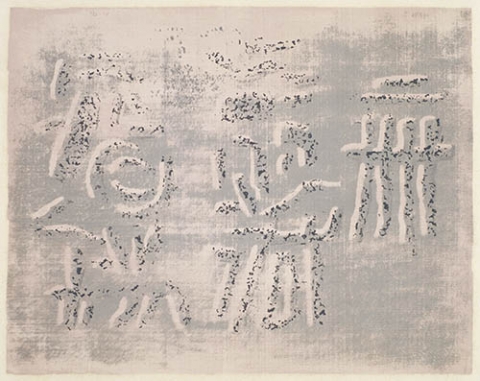

In terms of content we can establish - similar to the remaining graphic works and drawings - that he usually varied the motifs of his paintings and translated their content into the syntax of the silkscreen print. Only in the last works did he resort to drawings from the 1943 illustration series.

Translations of Earlier Paintings

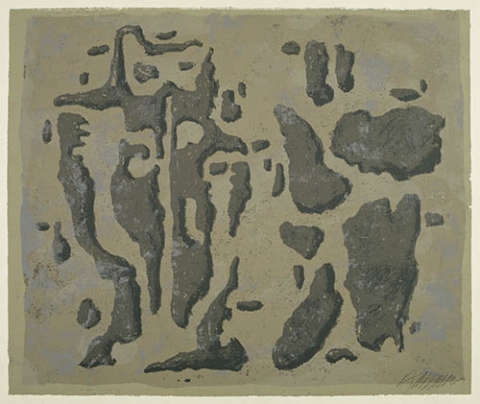

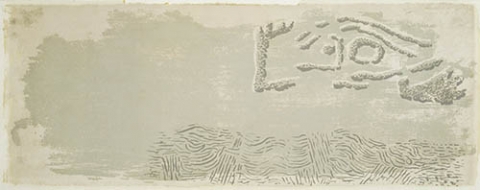

Among the most important artistic results in Baumeister's oeuvre of the 1950s are transfers of in part early sketches into paintings.

The serigraph enabled him to again grab hold of, expand, and optimize some his important formal inventions, whereby the latter had less to do with the sketch itself, than with the color, tonal effects, and clarity of the compositions.

The best examples include Africa leaves (1950, painting 1942), Runner (1952, painting 1934), Female Dancer (1953, painting 1934), Diver/Jumper (1954, painting 1934), Ideogram (1954, painting 1937), and Chess (1954, painting 1925!) as well as several leaves with motifs from the Gilgamesh series (1955, drawings 1943). Besides the new engagement with earlier motifs, Baumeister's serigraphs often dealt with motifs from current paintings, such as Phantom, Faust, Nocturne, Montaru, or Mo and several works with the title Aru.

Not least of all Willi Baumeister helped establish the artistic serigraph as a recognized original graphic method. His 1952 postulate was fulfilled:

Further development is not ruled out and it is critical that the painter and graphic artist follow our method.