_______________________________________________

By Petra von Olschowski, Stuttgart Museum of Art, 19 July 2013

Dear Ms. Baumeister,

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen.

Two images, black-and-white photographs, presumably taken in the late spring or early summer of 1955. In one of the photos, her father is standing in front of her; her sister beside her. He is planted there solidly, stably, legs apart, almost immovable, hands in his trouser pockets. He is ignoring the camera, staring past it to a distant point on his studio floor. Her sister, left leg angled playfully, is looking at her father with a slight smile. Her hands are placed behind her back, and she is wearing an elegant outfit, with pearls around her neck. She is taller than her younger sibling who is standing in the middle of the trio: Felicitas. She is the only one looking past her father to make eye contact with the photographer and thus the viewer. One sees a sensitive young face with an alert gaze, a delicate, fashionably clothed figure with a slightly sporty look.

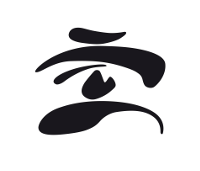

The second shot must have been taken shortly before or thereafter: Felicitas is standing alone in front of her father's wall of pictures, wearing the same clothes, in almost the same stance, only now her gaze is turned away to the distance. It looks as if her slim figure is casting a slight shadow on one of her father's pictures, presumably Relief Alt-Rosa (Relief on Antique Pink) - almost as if her silhouette were blending with the motif and she were growing into life from the Baumeister world of shapes. As if somehow she were emerging from the monochrome relief background, or disappearing into it. Immersing within it.

Two photographs. There isn't much more to find when you look for traces of Felicitas Baumeister. There are no publications about her, no essays, no information on the Internet; merely a few press releases. Only these two images can be found on the Willi Baumeister homepage, both taken in the year that Felicitas Baumeister's life was about to change. But here, in these captured moments, she doesn't know that yet. She has just passed her journeyman's examination in dressmaking at the renowned fashion salon Karg in Stuttgart, which her father is proud about, and where she meets her future husband Roland Karg. Four years previously - having completed her studies at the Hölderlin Grammar School for Girls - she had been to Paris to explore the fashion scene, after which she attended the Women's Technical College. Fashion: it was supposed to become her world. She also loves to draw and take photographs. But on 31 August 1955, Willi Baumeister dies and everything changes for her mother Margarete Baumeister, and for daughters Krista and Felicitas.

If you talk to Felicitas Baumeister today, an unbelievable 58 years later, about this moment in her life, her lips form some of the words that recur time and again, albeit in different shapes and variations: naturally, self-evident, necessary, a matter of course . She has, she says, devoted her whole heart to the purpose. This is a fundamental attitude in the family. And even the way she says it is so… self-evident.

She sits opposite me in jeans and a chic tunic, her father's pictures once again on the wall behind her, and even now she looks at you with those alert sparkling eyes (you can't see that they're blue in the photo). She smiles, openly, gently, naturally; she is approachable and above all so unbelievably young.

The purpose to which she has devoted all her heart since 1955 is the curation of her father's estate, Willi Baumeister. Here in this Museum, in this circle of friends and acquaintances, this is well known. But where else in the art world could you find someone who has been able to preserve work, reputation and renown amongst the public, the collectors, curators, museums, gallery owners, traders, scientists and artists without scandal or strife, without controversy or doubt at the highest level for many years, decades even; has put heart and soul into keeping the legacy alive, yet still remain in the background? At the very least since the death of her sister Krista Gutbrod in 1995, such a fate has lain mainly in Felicitas' hands and in those of her nephew Jochen Gutbrod. For me, the cleverest move in all her very level-headed and astute dealings was to transfer the privately-owned archive to the Stuttgart Museum of Art on permanent loan in 2005. Both generous and far-sighted. But more of that later.

Perhaps her actions spring from an attitude that Willi Baumeister describes in his theoretical work Das Unbekannte in der Kunst ("The Unknown in Art") quoting Goethe - in hindsight he could almost have included it in his book especially for his daughter:

Goethe to Eckermann:

"My dear young friend," said he, "I will confide to you something which may help you on a great deal. My works cannot be popular. He who thinks and strives to make them so is in error. They are not written for the multitude, but only for individuals who desire something congenial, and whose aims are like my own."

For Felicitas Baumeister, then, it was never about popularising Willi Baumeister's work, but rather about drawing in those whose aims are 'like her own'. She has never subjected herself to market pressure, or the weight of the zeitgeist. Were there ever crises, I ask. Actually no, she replies.

Many of you here today, ladies and gentlemen, already know the dates and facts. Even so, it is important to look back once more in order to trace the outline of Felicitas Baumeister, perhaps within the great shadow cast by Willi Baumeister himself.

The entry in her father's diary is succinct: Wednesday 26.4.1933, 4.30 am, a daughter born. No complications. Mother doing well, child normal. "Normal" at this time doesn't say much. Only a few days previously, Willi Baumeister, Professor of Advertising Art and Typography at the City College of Arts (the Städelschule) in Frankfurt, had received a letter from the new director, informing him that his services would no longer be required . The bleak years are fast approaching. Baumeister is obliged to clear his Frankfurt studio and, on 7 April, takes his wife and four-year-old daughter Krista to Stuttgart, to his mother-in-law's and brother-in-law's house in Gerokstraße. What now? he asks in his diary.

19 days later, his second daughter comes into the world in the middle of the Depression Era, as Baumeister writes to Schlemmer. No income (...) situation poor, with few prospects. The child was to be called Felicitas, happy fortune.

Willi Baumeister, considered a "degenerate artist" by the Nazi regime, ekes out a living for the family with typography assignments and projects for Kurt Herberts, owner of a paint factory in Wuppertal. Felicitas is a pupil at the Wagenburgschule, but when the house in Gerokstraße becomes uninhabitable during an air raid in 1943, the family moves to the Swabian Alps, to Urach, where Felicitas attends first primary school and then secondary school. As the front draws ever closer, the family seeks protection and asylum in a cave in the surrounding area. Eventually, in Easter 1945, the family decides to flee: their destination is the house of artist colleague Max Ackermann and his wife Gertrud on the Höri peninsula at Lake Constance. This is where the Baumeisters see out the end of the war, and from where they travel back to Stuttgart in late August 1945, with six cases of pictures and the manuscript Das Unbekannte in der Kunst when it becomes clear that there are opportunities for Willi Baumeister at the Stuttgart Academy of Art. In 1946 he becomes professor and Das Unbekannte in der Kunst is published in 1947.

In the copy given to his daughter Felicitas, he writes on 21 November 1947:

For my dear daughter Felicitas: adjutant, secretary with the good memory, finder of lost and misplaced notes, letters, keys, etc. Always ready to fold paper spills, light fires and occasionally issue a clear rebuke if the regime was in danger. Particularly memorable the Urach years, 1943, 44 and 45, when this piece was written at the four-sided table in the little living room. We saw all the seasons come and go. Despite the horrors surrounding us, we never lost courage (...)

Did it also require courage to take over coordinating her father's estate, and in doing so establish the necessary conditions for researching and preserving the works of one of the most important German, indeed European, artists of modern times? Felicitas Baumeister considers this only briefly, answers no; she, her mother and her sister had previously been familiar with his work. In the evenings, when he came out of his studio, her father would often bring the day's work with him and discuss it with her mother, herself originally an artist. From early on he had consistently photographed works and groups of works. And every year at New Year he would evaluate the year's output; judging it, almost. Some file cards reveal the mark good for important works. His criteria: A picture must haunt. He was convinced of the value of his work (otherwise it was destroyed), and he always allowed the family to be involved, says Felicitas. She describes how the whole family stood together in tears one day when the collector and doctor Ottomar Domnick purchased an important piece and it was taken out of the house.

Familial relations were loving and agreeable; Felicitas was very close to her sister. The two daughters were always of the same opinion when it came to questions about their father's works. The same goes for Krista's son Jochen Gutbrod today. This unity always gave her security, says Felicitas. So too did her friends and advisers - back then people such as gallery owner Herbert Herrmann, Baumeister's students or Will Grohmann, with whom she created the catalogue raisonné - with an extraordinary basic concept, one might add: classification by groups of works. If you ask Felicitas today about the most important successes, this is the first thing she mentions. Many more supporters, friends and advisers also came along over the years.

Shortly after publication of the catalogue raisonné came the first big international appearance: honouring Baumeister at the 30th Venice Biennale in 1960. When Felicitas Baumeister received honorary senatorship from the Stuttgart Academy of Art three years ago, Professor Hans Dieter Huber made particular point of this in his speech: Felicitas Baumeister did not only feel responsible for preserving her father's legacy, but also displayed fine curatorial skill and conservational sensitivity by making every effort to ensure that his pictures and drawings could be presented framed and in faultless condition.

Felicitas Baumeister herself says: The only thing we could do was exhibitions.

If you ask about her strengths, Felicitas replies that she is both strong and guarded at the same time. One mustn't forget that she also cared for her sick mother. Meanwhile, I had also been married for 20 years and worked a lot with my husband, she says, and laughs again.

For almost sixty years, she has also ordered, sorted, described, evaluated, archived, transcribed, exhibited, conveyed, publicised, curated, listed and much more. Never losing sight of the whole. More importantly, she has anchored her father's work in the modern history of art and kept interest in it alive in the younger generation. This too she considers merely natural, but one need only look at the disputes surrounding the case of Baumeister's friend Oskar Schlemmer to know that it isn't. Cleverly, she has sought a network of partners - not only here in this region, but also nationally and internationally. For example, I would like to mention the three-part exhibition to celebrate the 100th birthday of Willi Baumeister in Stuttgart and at the National Gallery in Berlin, as well as retrospective exhibitions in Madrid and Munich in 2003/04.

The next project is the publication of Willi Baumeister's letters and editing his diaries; Felicitas would love to thematise the tennis player motif in the work. Currently, she is busy preparing for the exhibition Willi Baumeister International, which is opening here at the Museum of Art in October 2013. For the new research generation wishing to focus on Willi Baumeister, she has - together with Hadwig Goez, among others, who as a permanent staff member has played a key role in archive work since 2000 - transferred the Baumeister archive to the Museum of Art and thus succeeded where many curators have failed: she has shared the archive and made it publically accessible. Her trust in the future, and in future generations, is immense.

And what of Felicitas herself? She still has a fair few projects in mind, she says. One would expect nothing less. She would have liked to try her hand at designing glass windows, actually, but she's putting it off for when she's between 90 and 100. In between her continued work in cataloguing the estate, there is still just about time for Sunday strolls on Wangener Höhe, for her interest in archaeology, for her commitment to the Stuttgart Academy of Art (for which I am particularly grateful) and for the city of Stuttgart itself, with its cultural and architectural heritage. Somehow, no one really believes in the year off that Felicitas wants to take after the exhibition at the Museum of Art. She is too keen to do so much more. Like using her excellent memory, for example, to 'ensure knowledge', as she puts it.

Before leaving the paradise on Gerokstraße this afternoon, I ask about her favourite pictures. Felicitas goes to the Willi Baumeister room with all his little gems and great riches, his unique finds, archaeological treasures, masks, collected pages from esteemed artist colleagues, drawings and pictures. She pauses before two paintings from the series Wachstumsbilder (Pictures of Growth). Here the light surface is gradually placed on the dark background, so that the outlines are only determined right at the end... I think that's really important. It's quite unique - in the effect, in the movement, she explains.

I think about the outline of the young woman standing in front her father's pictures. The dark shapes of the Pictures of Growth series whir past in the almost white space, chasing each other, flying, floating, pulsating... And she is standing before them. Calm and clear-sighted. Felicitas: the adjutant, the happy fortune.