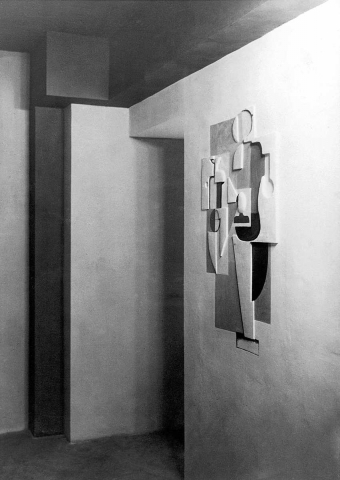

The human makes a wall. The wall gives him the surface. The surface is the primordial means, the first elementary medium of painting. After the war, I produced simple pictures, proceeding from the wall, with the wall. Parts of it were raised relief-like, others were two-dimensional. I called these pictures "wall pictures". ... At the time I envisioned a new architecture that was not yet available as a carrier of these wall pictures, which were formed out of the elementary media.

Thus wrote Willi Baumeister in a 1934 manuscript for Eduardo Westerdahl's monograph about a style dating back ten years that he nonetheless never lost sight of because he based nearly his entire production on the principles of the surface, simplicity, and originality.

The 'wall pictures' had their beginnings in 1919 - immediately following Baumeister's return from World War I. Along with the wall pictures, 'heads', a few planar compositions, and other figural pictures also comprise this significant work period that characterizes the years up to around 1923-24. Schooled on a new understanding of form taught in Stuttgart by Adolf Hölzel and prevalent among many of his pupils, Baumeister invented a formal approach that represented not only his artistic beginning, but also his breakthrough of the 1930s. What is more: he achieved international recognition with these works and laid the foundation for a 35-year development of abstract painting.

Exhibitions with International Recognition

In March 1922 the young artist exhibited jointly with Fernand Léger at Herwarth Walden's 'Der Sturm' gallery in Berlin. That year he also showed works in a solo exhibition in Hanover and was introduced in an article published in Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant's French journal, L'Esprit Nouveau:

If Willy Baumeister's work merits special commentary here, it is because this artist admirably strives for clarity. His paintings and "wall pictures" bear no trace of sentimentality. The relationships of angles and planes are the sole means of expression. He distinguishes himself through a sobriety and economy that are greatly to his credit ... If the rigidity of the abstraction appears strange to many today: we are certain that this is the right way to achieve the desired, generally effective monumental art that waits for the spaces of a brilliant architect. (Translation from exhibition catalogue, Berlin National Gallery 1989)

For the German Werkbund's first exhibition in Stuttgart in spring 1922, Baumeister executed three wall pictures for the first time, which were directly integrated into the exhibition architecture by architect Richard Döcker (1894-1968). For the critic of the 'Stuttgarter Neues Tagblatt' the interplay of architecture and painting was "the artistic feat of the exhibition" (April 5, 1922). The much acclaimed cooperation of the two artists was repeated in 1924 during an exhibition of the same name in Stuttgart.

In 1921 the wall pictures appeared in an art magazine for the first time. The 'Kunstblatt' critic Paul F. Schmidt called Baumeister's art a natural response to the unrestrained quality of expressionism. And in 1922 Stuttgart art critic Düssel spoke of clarity, terseness, and formal completeness. In public the wall pictures were seen as an expression of a new - consolidated - cultural era, which after the war seems more than understandable.

Organism and Law: The Path to the Wall Picture

Even before World War I, Willi Baumeister was concerned with clarity of form and depiction in his early works. Inspired by cubism and Paul Cézanne, but also under the influence of Adolf Hölzel, he, beginning in 1910, reduced the natural impressions of what he saw to simple and two-dimensional elemental forms such as the circle, oval, and rectangle and gradually eliminated everything that suggested spatial illusion and aerial perspective.

In 1919 Baumeister immediately resumed this tendency with the wall pictures. The primacy of the surface systematically led to the direct reference to architecture and ultimately - at the two Werkbund exhibitions in 1922 and 1924 - to integration into the wall. Even so, apart from these special solutions, the wall pictures always remained 'mobile'. They were not a matter of wall reliefs or frescoes because their composition and formal development was - as Baumeister put it in 1934 - certainly related to the wall and thus the surface, but not bound to a specific wall.

The Hölzel Circle had already dealt intensely with the subjects of the 'wall' and 'elementary media'. Ida Kerkovius, Johannes Itten, Herman Stenner, Oskar Schlemmer, Willi Baumeister, and others also dealt repeatedly with the subject of the human figure, but always with the aim of overcoming what they saw as the false illusionism of naturalistic representation. As such the wall pictures in Baumeister's oeuvre are exemplary of the 1920s. The artist did not work with figuration (as he briefly did later around 1930 and again rejected), but rather with visual building elements that concerned figures as well as machines. The wall pictures no longer had a representational function.

With the paintings of the early twenties, Baumeister wanted to bring back the 'fundamental laws' (Will Grohmann) of art and in particular of the human form to expression - or better still, 'to work them out'. Herein the proximity to cubism, to Cézanne and to Hölzel also appears, because in the wall pictures Baumeister worked with geometric models, with colors and surfaces, their contrasts and penetrations, with emphatically haptic surface structures, rhythms, and tensions. Baumeister's aim was to represent the essential behind the arbitrary appearance. Thus Grohmann is right on the mark when he calls the wall pictures the 'commandments of art'.

Objectification and Synthesis

Baumeister's works of these years clearly reveal not only a tendency to objectify and deemotionalize art, but also a new orientation toward connecting the once-separated arts. As Baumeister himself emphasized in different contexts, the division of the fine and the applied arts had become insignificant for him (see articles on Typography and Frankfurt Professorship.)

Picture and wall - picture and architecture - picture and space - and ultimately: picture and environment! These were also catchwords of the Werkbund and Bauhaus artists with whom he was in close contact. Baumeister's wall pictures were never just an artistic-formal exercise, but also always an avowal for the inclusion of art into everyday life.

Architecture in 'Boomtown' Stuttgart

In this context it is useful to look at the situation in his hometown Stuttgart immediately following World War I. Since the 1880s the city had been immersed in swift development. The issues of building and living were important factors in public life. In addition, the new central station (architects: Bonatz & Scholer, 1914-22) was put into operation and was to give a new sense of purpose to the old railway-track platforms located in the city center. Between 1919 and 1927 machines and workers defined the scene not only on the railway station construction site, but also on the cleared grounds. Human and machine also became a theme for Baumeister, art and handcraft another. New buildings and unseen bustle in a transforming society confirmed his belief that art and life were to be seen as a unit, that a work of art should not be produced or considered in isolation.

This thinking took on exemplary bearing for Baumeister in architecture, in which the most varied arts came together in an everyday situation. The interaction of the painter and the space in which his works of art were to stand or hang had attained an importance that for many extended beyond the artistic. He himself took this task into account in his collaboration with Döcker in 1922 and 1924, but especially somewhat later in his participation in the Stuttgart exhibition Die Wohnung (The Dwelling) in 1927 with the Weissenhofsiedlung (Weissenhof Estate).

The 'Wall' Theme after 1924

Even though Baumeister gave up the wall pictures in the narrower sense around 1924, he remained connected to the theme throughout his lifetime. First, he retained the geometrical severity until 1929-30. The reference to the surface determined all his works to the end as well. Moreover, from a physical standpoint, the wall-like and the wall as structure appear repeatedly in many later work phases by which he continued to treat the surface of a great number of his paintings and graphic works with, for instance, sand and putty, wood or film, or with combing and frottage. He also continued to use relief structures and developed them further.

Not least of all, picture titles such as 'Steingarten' (Rock Garden) (1939), 'Tempelwand' (Temple Wall) (1941), 'Palast strukturell' (Palace Structural) (1942), 'Linienmauer' (Line Wall) (1944), 'Figurenmauer aus Gilgamesch' (Figure Wall from Gilgamesh) (1945), oder 'Blaue Mauer' (Blue Wall) (1952) demonstrate that, for him, the artistic approach of the 1920s in which:

The wall gives him [the human] the surface. The surface is the primordial means, the first elementary medium of painting.

remained a guiding principle until the end.