Starting Out and Modernity

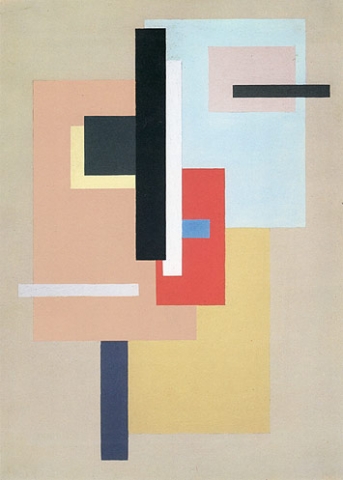

In his second period of production, after World War I until the end of the 1920s, Baumeister resolved the traditional connection between form and color. He increasingly reduced and abstracted his representational painting in the direction of geometric form - elemental form in Baumeister's view.

With the end of World War I tremendous social changes also manifested themselves in the arts and architecture. For several years beginning in 1919-20, Stuttgart became one of the centers of artistic transformation in Germany along with Weimar/Dessau, Frankfurt am Main, and Berlin. Many artists - including Willi Baumeister - saw the change as a opportunity for a radically new world of form.

In Baumeister's work this phase was marked by an emphatic striving for modernity. Many understood art as a visualized attitude of a new culture. For Baumeister this meant, on the one hand, departing from historicism and, on the other hand, seeking expressive means capable of reflecting the societal transformation, if not even leading the way as art of the avant-garde.

In the Frontier Region to the Nonrepresentational

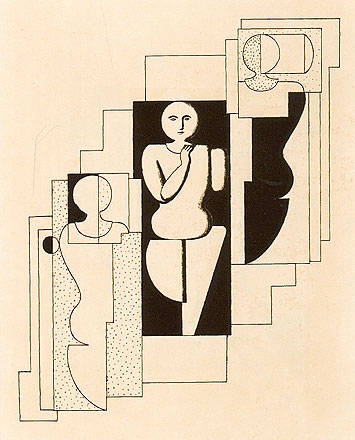

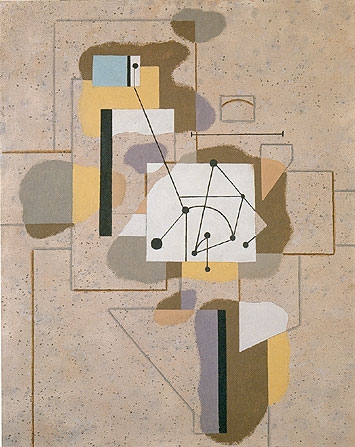

Baumeister's themes between 1919 and around 1927 focused on the human figure. In seeking a modern attitude, he and many of his colleagues turned to abstraction. On the threshold to a nonrepresentational art, Willi Baumeister - parallel to artists such as Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian - tread a path that granted form and color complete autonomy.

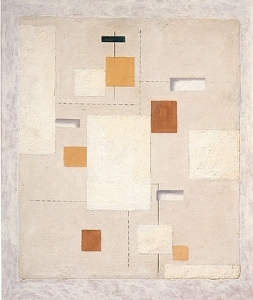

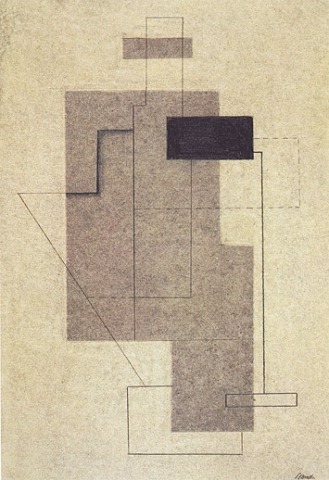

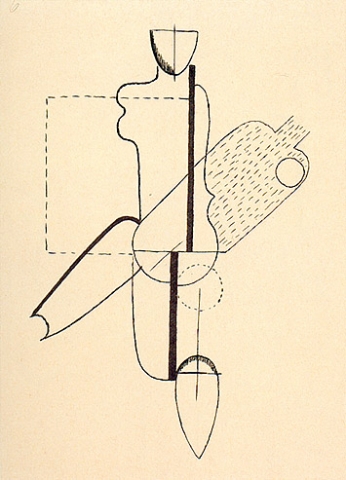

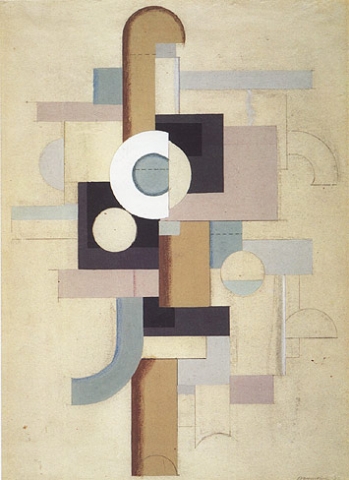

The work group Planar Energies (1920-26) illustrates Baumeister's efforts to achieve a taut, purely constructivist balance of formal media without any representational qualities. At the same time the title of the drawing Seated Figure (1926) illustrates that he was dealing with figuration, that is, with articulating a compositional principle that also had a human and thus a social dimension.

The relationship between construction and (human) figure becomes especially clear in the wall pictures.

Wall Pictures

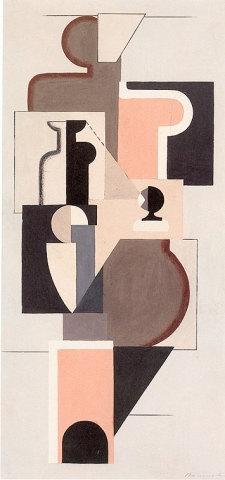

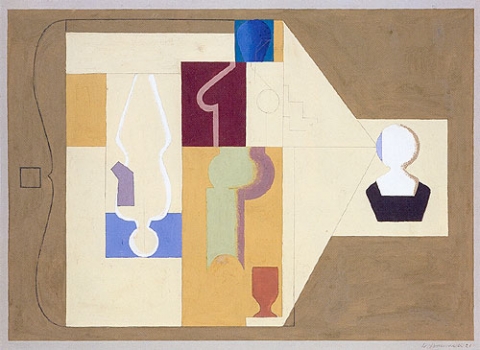

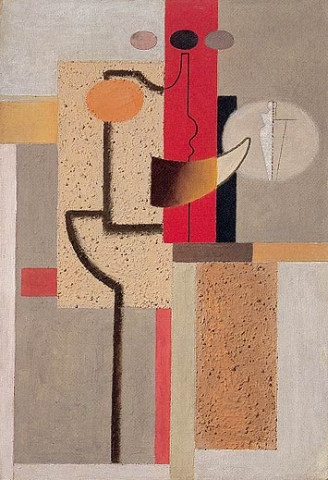

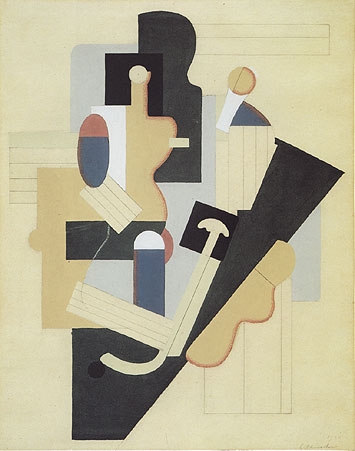

In the so-called wall pictures Willi Baumeister's personal style emerged for the first time. In them he arranged figural compositions based on geometric formal elements such as the square, triangle, and circle into - real or apparent - relief structures. With these architecturally related components he quickly received international recognition. In contrast to German expressionism, from which Baumeister turned away, this art had nothing mystical about it. It aimed at remaining objective and structurally and practically strove for a connection to architecture: At the time I envisioned a not yet available, new architecture as a carrier of these wall pictures (Baumeister 1934).

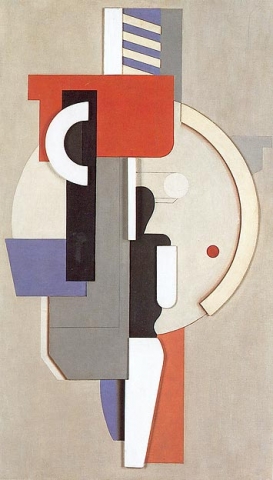

For Baumeister the human figure in its stereometry became a symbol for the fundamental construction of everything visible. His notion of art in this period united all his works - the representational-abstract and the nonrepresentational. Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal, round and rectangular elements complement one another to produce an ideal form. Axial or central focal points lend the compositions stability. With color contrasts Baumeister underscored the relief-like structures that he emphasized in oil paintings with the use of papier-mâché, pieces of cardboard or plywood, or metal foil and demonstrated his affinity with cubism.

New Human, Sports, and Machine

Baumeister saw the tectonic construction of pictures as synonymous with the construction of a new world that was based on elemental forms: simple and clear. That to this end he frequently invoked the god Apollo, who stands for moral purity and moderation as well as for the arts, underscores this intention.

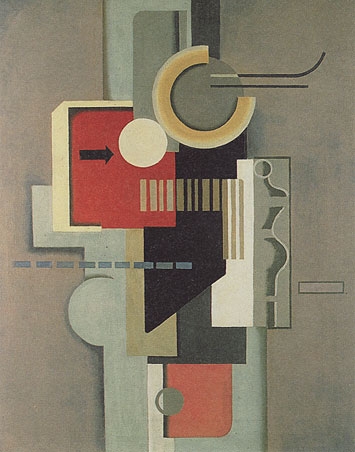

In the work group of machine pictures and in many of his artist and sports motifs Baumeister also gave form to the notion of a modernity based on an elemental structure. Among the latter this is already suggested in the Chess Players (1924-15) and in Hockey (1924), but - like the Painter - first becomes a distinct theme toward the end of the 1920s.

The work group human and machine - typical of the mid 1920s - exhibits a picture construction similar to that of the wall pictures. The figural components remain recognizable, but their immediate reference to the human figure either retreats behind wheels and casings ( Machine with Red Square, 1926) or - as in Machine (1925) - is almost completely eliminated. As in Figure with Circular Segment (1923) Baumeister stressed the relationship between human and machine and their interacting energies over the human figure with a screw in the axis.

In the Right Direction

This work segment had elementary significance for Baumeister's production. The successes showed him that he was on the right path. Many technical and thematic aspects that he developed during this time would appear in his work repeatedly. These include - along with the reference to the surface and the search for elemental states in art - a relief-like construction and emphatic materiality through the use of additional media (later sand and putty).

Some aspects certainly emerged around 1925, but first became more apparent a few years later, like the somewhat more active line in Chess (1925) or the occasionally stronger emphasis on line and contour in contrast to color surfaces.

To the previous work phase 1905 to 1918