I went to Baumeister because he taught in a modern way and because, in contrast to Beckmann and Delavilla, he worked abstractly. His class was large (two rooms) and Wichert was strict in admissions. I submitted work samples from a preliminary-class semester in Offenbach, for which he accepted me (fall 1929 to the beginning of 1933). With Baumeister I had free drawing, nude drawing, figure drawing (five-minute poses from models that I chiefly obtained), compositions with cut and torn paper, cloth, thread, alphabetic characters, also photography and painting instruction, where at the beginning he had us mix black and white tempera in four different small bowls with green, blue, red & yellow to arrive at the famous colored grey tones. His unframed wall pictures were his artistic conviction then. I attended the photography class of Instructor Biering (who spoke the Saxon dialect and was, as wicked student-chatter claimed, either gruff because he had bile ailment or got the bile ailment because he was gruff) to make reproductions and my first portraits with a studio camera. There was no exposure meter yet, but two darkrooms with three enlargers. I also twice used the spraying procedure in the same studio with nozzle and oxygen apparatus to become familiar with the effect of stencil work.

I was occasionally in the typography department (the composing room of Instructor Albinus, an advocate of absolute lowercase writing - he, too, had to leave the school in 1933) for a few poster designs with an interactive arrangement of cutout alphabetic characters. Baumeister: It must be succinct. In addition to the class Willi Baumeister had his own studio that we students were allowed to constantly enter and in which I always saw him at the easel painting his sand-ground pictures. He gladly explained his technique and let us do similar things in instruction. He could converse with us while he painted and one sensed that an association flowed in from somewhere that moved him subconsciously.

Dr. Gantner's art history instruction was very popular, but the art philosophy lectures that Willi Baumeister held every morning are unforgettable. When he came in around 10 o'clock, a student always kept a match ready for his cigar. Then he corrected our works and also occasionally spoke about a book that someone was reading at the time. He had a splendid memory and knew by heart all the names that appeared in my Dostoevsky book.

It was very typical of his instruction that he arranged discussions with other classes (e.g. Professor Schuster's architecture students) and let us participate in other classes as auditors. From one teacher (the former student Wolpert), we occasionally received a very non-doctrinaire pictorial instruction in letter drawing. Also to be emphasized is that the students of the Frankfurt school were fortunate to draw important impulses from the very modern library with a lovingly set-up archive in the house next door, where I often went to read the modern periodicals The new Frankfurt (Das Neue Frankfurt), Querschnitt (The Cross Section), and so on. The director was Dr. Diehl from my hometown Pirmasens.

In 1969 I tried to get into contact with my Frankfurt schoolmates, in connection with a Baumeister -student exhibition like the Stuttgart student exhibition in Wuppertal, but it did not succeed. Among others, my class included Lotte Stern, Erika Wachsmann, Lotte Eichelgrün, Grit von Fransecki, and the golden child Fanny Beyer (these two often demonstrated a tap dance together during school excursions). Then [also] the students Ernst Fay, Fechner, Wittekind, Börner, Kramer, Weinholdt, Hof, and Jo von Kalckreuth. Shortly before 1933 Jo was dismissed because of his disposition and because he sometimes came too late to school, which very much infuriated Baumeister and his colleague Peter Röhl. One instructor for mural painting was called Bäppler, whose Frankfurt dialect often gave rise to parodies.

At the time Baumeister was too ironic and often sarcastic for me (I was 18 years old and very serious) so that my (merry) fellow student Fanny said to him: Yes, but now you have to give Marta a serious response to her questions! He always encouraged us to visit him in his studio, where he worked on his pictures with sand coating, but I often felt jealous when I encountered the pretty fashion students there. My sister Madeleine, who sometimes drove him in our Opel and brought him to the lookout in Ginnheim, had an easier tone with him. She was one of the first chauffeur girls and Willi Baumeister happily talked about engines with her. Antennae and other (bizarre) innovations also interested him. Baumeister commentaries: During a 1932 exhibition at the Frankfurt Art Association, journalists asked him what he might have to say about a particular picture, to which he replied with his well-known sarcastic humor, I was thinking about pea soup at the time. If in nude drawings we stressed the sculptural too little and the contour too much, he said: The human is a sausage doll, and if we painted or drew a portrait too naturalistically, he would say: Right, the longer one paints around, the more similar it becomes!

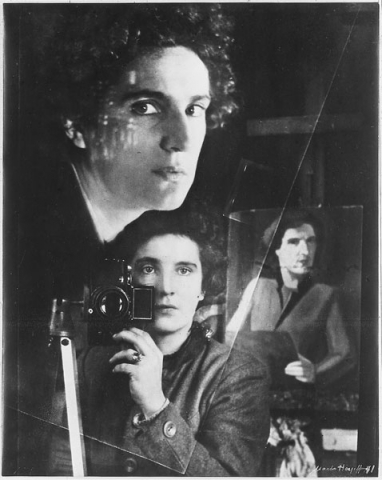

Willi Baumeister tacked all the important invitations to matinees and opening receptions onto the blackboard so that I saw the abstract and surrealistic films by Fischinger, Hans Richter, and Cocteau in the Das Neue Frankfurt Union and the met the filmmaker and dada-successor Ella Bergmann-Michel. During instruction Baumeister also showed us the works of Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, and Herbert Bayer, who were the first to raise photography to the status of a modern art form. Particularly Moholy-Nagy's book Painting, Photograph, Film (Malerei, Foto, Film, 1925) made a great impression on me as an art student. I later took up photography alongside painting, like others make etchings or lithographs.

Professor Willi Baumeister saw artists and researchers as equals. The artist works like the researcher, he makes discoveries. He urged us to gain insight into modern science, about which he explained a good deal to us. He saw an important artistic task in the experiment and its technical accuracy. In instruction we learned to let imagination and technique intermesh through nonrepresentational pictures in photographic media (photograms).

When my teacher lost his lectureship in April 1933 through the Nazi regime, I left the art school - I rejected his successor Windisch and was unable to use what I had learned since neither my style nor my ideas (cultural Bolshevism!) were approved of. I was thus unemployed except for the occasional jobs for Frankfurt illustrated [magazines] (picture series of photomontages).