Willi Baumeister single-mindedly developed an impressive, very personal visual language that was unique in German art immediately after 1945. The recognition he received in the postwar period, in particular in the 1950s in Germany and abroad, was correspondingly strong. On the one hand, there are impulses from a variety of his representational work periods. On the other hand, there are also densely packed abstractions that characterized Baumeister as an outstanding nonrepresentational artist. Without a doubt, these paintings became the most renowned and were immediately linked to his name by a broad public.

Delight in the Revival

Intellectually, the end of the war was a new start for Willi Baumeister. After years of isolation, he could practice his art freely again (see Biography). Artistically, however, there had been no standstill for him during the years of the Nazi regime, so that he now seamlessly continued the development of the preceding years. In a time that was distinguished by many exhibitions, travels, publications, and intense teaching activity, Baumeister was exceptionally productive.

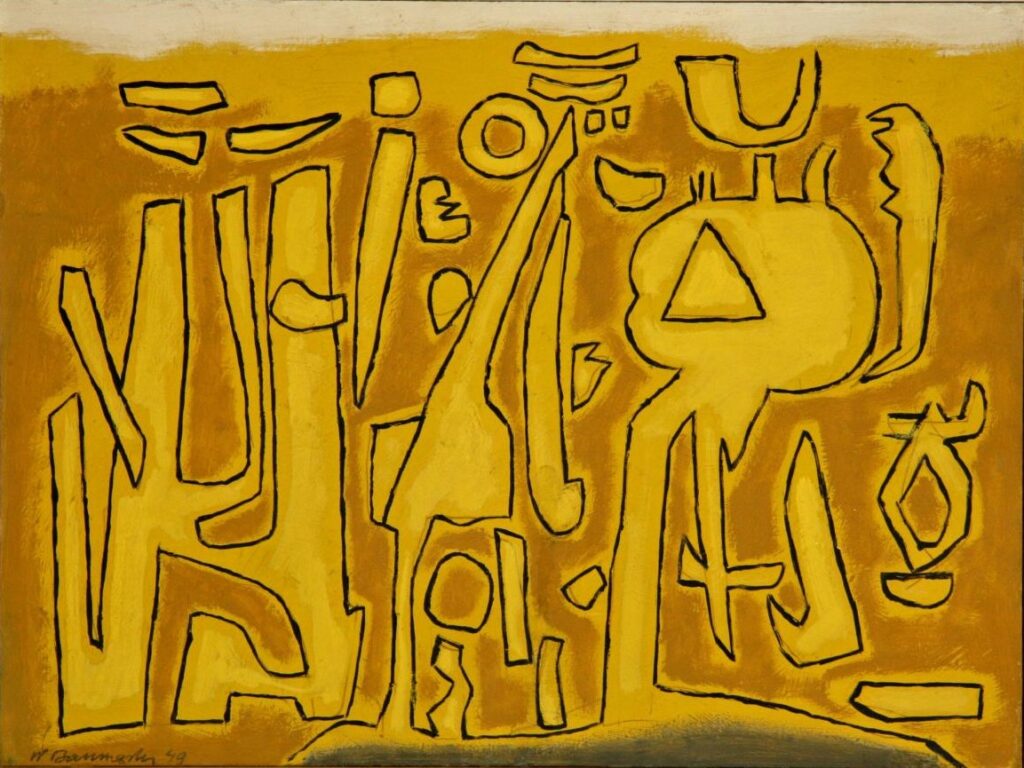

Surprisingly his palette had already lightened up before 1945, as the “Sun Figures” and “Line Wall on Yellow” (both 1944) show. Baumeister undoubtedly had hoped that everything would take a turn for the better. To these figuratively-conceived but borderline nonrepresentational paintings he now linked different groups of landscapes and Wall Pictures. In their bold colorfulness and delight in movement, “Maya Wall” (1945), “Animated Landscape” (1946), and “Jour Heureux” (Happy Day, 1947) are images of liberation. Titles such as “Cheerful Movement”, “With Air Figures”, “Vital Landscape”, or “In Colored Clouds” are also indicative of this phase.

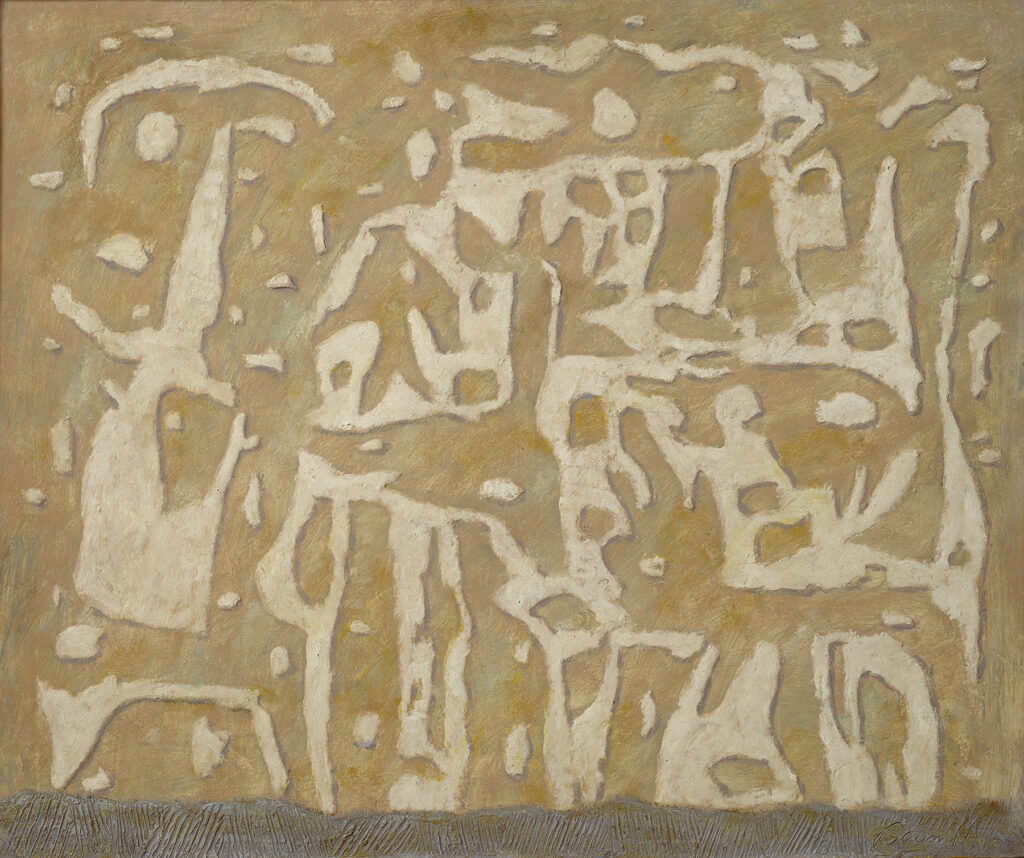

With the new Wall Pictures and their ornamental interlocking of forms and colors, Baumeister formally continued the basic idea of the Africa, Callot, and Perforation series of 1942. He had already begun the extraordinarily painterly treatment of surfaces around 1936. The landscapes of 1947–48 display traces of the 1938–39 Eidos pictures. The Stone Garden theme from 1939 and works with glaze spots from around 1940 also resonate in the Animated Slope (1949).

In contrast, the strong relief-like construction of those years now mostly gave way to a greater lightness and two-dimensionality. This is also evident in Animated Slope and a few Harps. In them Baumeister varied the rock- and scratch-drawing theme that had occupied him since around 1930. There are numerous other examples of this reconsideration. They evince the continuous change in Baumeister’s work, rather than a regression.

Primordial Creation as Symbol for the Reconstruction

Thematically he still explored the archaic world, whose eternal validity appeared all the more important to him in the period of reconstruction and newly gaining a sense of identification. The taking up and newly interpreting of available concepts exists throughout Baumeister’s entire oeuvre, but is especially apparent at this time.

Inspired by a small object in his own collection, the “Aztec Couple” of 1948 exemplifies this sort of artistic reconsideration – as do several Giant, Epoch, and Peru motifs. But it also symbolizes the primordial art and human at the beginning of creation and the creative act. This outlook took on particular weight during Baumeister’s professorship between 1946 and 1955.

Emphasizing the Moral Standpoint

During the war Baumeister turned intensively to drawing and produced several cycles on mythological themes and the Old Testament. He now lithographed a few of these cycles and arranged them into the “Salome” (1946) and “Sumerian Legends” (1947) portfolios. He also transferred numerous other motifs of his drawn and painted works of earlier year –not just of the wartime – into the medium of lithography and, beginning in 1950, into silkscreen prints, thus making them accessible to a broader audience.

In contrast to the drawings of 1943–44, Baumeister used color in some lithographs to stress particular pictorial components or to reveal different effects. But he also used it in the original graphic work to vary some ideas. With the aid of color and the frottage technique, he lent many graphic works a painterly quality whereby he essentially turned many leaves of this phase into a media between drawing and painting. In this context, he also turned to the relief as an expressive form in the graphic prints, which remained an exception in the paintings between 1945 and 1949 (e.g. Brown Relief Picture from Gilgamesh, 1946).

The aims that Baumeister had pursued with his drawings during the war years were still valid now. Despite the demise of the Nazi dictatorship, the issues of power abuse and resistance, faith, and humanity had lost none of their importance. The lithographs and portfolios offered him the chance to once again intensify his standpoint with artistic means.

The Figure as a Measure for Art

In contrast to a few of the purely nonrepresentational efforts of the 1920s and 1930s, essentially all the paintings in the first years after 1945 remained – in varying degrees of abstraction – committed to the figure, if not just the human figure. This would change only occasionally in the last five years of his production. Even so, new pictorial ideas emerged in the following phase that would typify Baumeister’s aversion to every form of standstill.