Klaus Erler (born 1926) attended Baumeister's class from 1947 to 1948. From 1958 to 1985 he was a graphic artist in various advertising agencies. He was also active as an independent painter.

How I came to Baumeister: in 1946, I first began to study architecture in Stuttgart. Due to the general destruction of the time, my idealism, considerable drawing ability, and formal imagination were the mainsprings that lead to this decision. But it soon turned out that the art historical lectures, especially those on modern art, began to grab my interest more strongly by far than the lectures and exercises on building. Since I had always painted (chiefly watercolor), I felt an ever-stronger artistic impulse from the art lectures, especially from Prof. Hans Hildebrandt, so that in January 1947 I decided to switch to the Academy of Arts.

I became acquainted with some of Baumeister's students (including Gerdi Dittrich and Jaina Schlemmer) who encouraged me to request admittance to his class. The students simply took me along to a critique hour in the class, where I tacked my first abstract watercolor to the wall with the other student works. I called it le rouge et le bleu [the red and the blue], because it contained lively red color bands that were penetrated by blue peaked crystalline forms, made a bit in imitation of Franz Marc, whom I glowingly admired at the time. I do not exactly recall Baumeister's comments on this experiment; he probably found it too expressionist. But he must have granted me some goodwill, since after he asked Gerdi Dittrich privately what she thought of me and whether he should take me on (and she positively encouraged him), I was accepted. At least that is how Gerdi Dittrich described it to me later.

In the beginning there was a thoroughly private tone in all these strivings and all these decisions, a wonderful atmosphere of giving and taking, a warm human closeness that also included personal visits with Baumeister in his familial circle. As such I could also participate in the critiques without being an officially enrolled student. But I found Baumeister's demonstration with prints by other modern masters almost shockingly revolutionary; for instance, a Mondrian picture was shown and discussed that ignited profound discussions, whereby Baumeister also esteemed Mondrian as a modern great artist and explained his achievements to us. This discussion went even further into the private sphere, by which Baumeister more by chance, was also present and again confirmed his point of view to Mondrian's advantage.

My enrollment first took place in winter semester 1947-48, following an internship as a painter, which was required by the Academy Direction and which I completed in summer '47.

Now began an intense period of painting, research, practicing, and designing, and always with regard to Baumeister's power of judgment and the now greater number of fellow students in the class. When I once spoke to the class on the artistic state in the sense of modern physics, that it was defined by an energy gradient, I was laughed at. But Baumeister, who put a only slight damper on my scientifically inspired élan, basically justified my point of view... It did me good to be taken seriously on this point by a master.

Still, in the class I was gladly teased some with my Bullet-Flash pictures and affectionately mocked with the question what my energy gradient was up to. On another occasion, though, Baumeister himself also brought up an apt example of the character of the artistic state. When he was asked when it was that he could best paint or put himself into the artistic state, he replied that for him it came to a creative push, for instance, if he was looking forward to a theater performance or something else interesting and then the event would for some reason not take place. If he was disappointed and sat down at the easel in this state, [his] painting would go especially well.

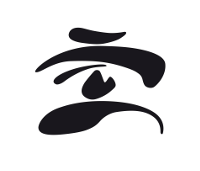

He once criticized a student...who presented heavily color-encrusted pictures in a thick impasto on canvas as too extravagant in paint consumption and intention (whereby he consciously neglected the slightly surreal horse motifs). In contrast, he praised my casually tacked up sign-like studies that were painted in India ink on thin white and yellow wastepaper. [He found] they were more effective by the economical use of materials alone. But pictorial asceticism was not to be taken too far. Constructivist design, such as that by Max Bill, he generally found too thin, as he once said with regard to me...

(From a letter to Wolfgang Kermer dated April 16, 1986; quoted from Kermer 1992, p. 186 ff. )