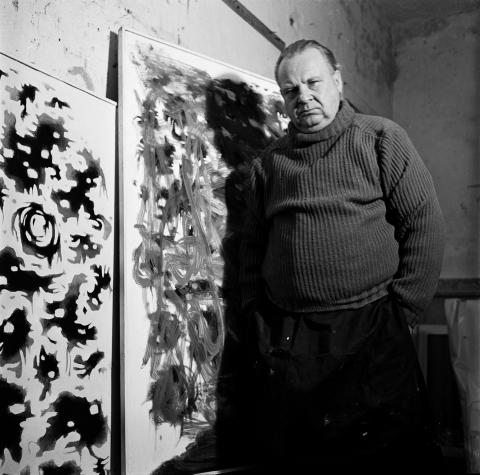

Completely different preconditions existed for Willi Baumeister's professorship at the Stuttgart Academy of Arts after World War II than for the teaching activity in Frankfurt between 1928 and 1933.

Baumeister himself laid the foundation for the new teaching assignment: with the professorship in Frankfurt he had demonstrated that he was prepared for the task in pedagogical terms. There was also his irreproachable behavior during the inner resistance to the Nazi regime. His paintings and lithographs between 1933 and 1945 proved that despite the temporary painting prohibition he had delivered and would continue to deliver a meaningful contribution to the development of modern art. And finally, his manuscript for the book published in 1947, Das Unbekannte in der Kunst (The Unknown in Art), provided evidence that he had important things to say as a theoretician of a new, non-compromised art.

On the Surface Again

In 1946, after the experiences of the first half of the century, Baumeister felt obliged to overcome the traditional and to open himself to the new - the unknown. This found approval among those who approached him soon after the war's end to apply for the office of Stuttgart Academy Director or to teach a painting class.

After the Baden-Württemberg Cultural Minister Theodor Heuss decided on a teaching position for Baumeister in January 1946, the artist was called to the Stuttgart Academy on March 16, 1946.

In 14 days, it will be 13 years since I was brusquely discharged [in Frankfurt]. I could be of the opinion to never again come to the surface... What will the office bring? (Diary, 3.16.1943)

First appointed to a teaching assignment, in November 1946 he was made an official professor for lifetime and taught a painting class until retiring as professor emeritus in February 1955. He took on another teaching assignment for an additional semester before he died in August of the same year.

Beginning Under Adverse Circumstances

On August 15, 1946 Baumeister and his colleagues began instruction in the badly-damaged buildings of the former School of Applied Arts near the Weißenhof Estate. He partially held classes in his studio, which was also housed in a ruin. Among the new teachers, Baumeister was the only one who stood close to the Bauhaus and also incorporated its principles into instruction. Moreover, he was the only one who subscribed to non-representational art unconditionally, which did not exactly strengthen his position within the philistine academic environment (Kermer 1992).

The Creative Angle

Between 1947 and 1955 Baumeister made numerous comments on his art, art in general, the discussion about figurative art and abstraction, and much more (see quotations and writings). They all - beginning with his writing The Unknown in Art of 1947 - illustrate Baumeister's pedagogy, with which he occasionally ran into opposition from colleagues.

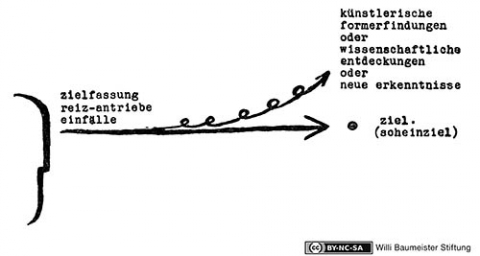

The most interesting example of this is the thesis of the creative angle. Baumeister believed that the things that the artists formulated as their goals were only fictitious goals - at best stimuli on the path into the unknown through which they (the artists) finally attained their actual - not foreseeable and not plannable - artistic result. In his own clarity, Baumeister visualized this by means of a concise sketch.

Art as Process - Emptying Instead of Teaching

Baumeister's idea that art results not through a preassembled plan, but during work, was one of the basics of his instruction. A second was his inimitable ability to represent artistic circumstances understandably and vividly; the third:

The teacher has to empty, not to fill with his formulae / [He] ultimately has the task of bringing the student into the artistic state through cleansing, through emptying. (1943)

Baumeister did not consider it his task to lead the students in a specific direction, but to make them exclusively familiar with the technical basics of artistic work, equip them with a critical thinking, and finally prepare them for the art market. Here the pragmatist in him came to light, who from the outset granted art a firm place in everyday life and who did not distinguish between fine and applied art. (On this subject, see also the wall pictures and typography)

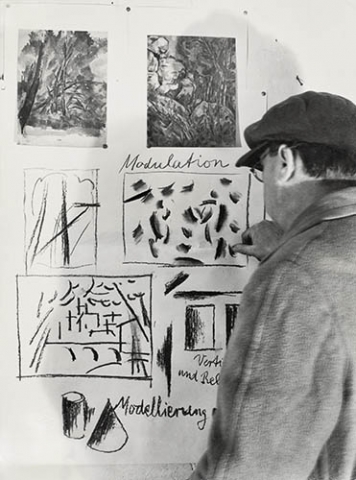

Baumeister's System

With all the latitude - no freedom! - that Baumeister allowed his students, with all his stance for non-representational art, and with all the searching for the unknown, for the neutral point from which every art finds its departure and every artist his or hers, there was naturally a pedagogical concept with which Willi Baumeister revealed that he was by no means the great outsider:

in my class there is the study of the nude human. the main thing, however, is the great lesson of elementary media. elementary media - and nothing else - form the bases for architecture, interior design, stage design, mural painting, commercial art..., textiles, sculpture, metal design, and so on.

since the study of elementary media is not yet specializing, the student receives an introductory training with a very broad basis... in social-economic terms, free art is largely unprofitable. the independent young artist who waits in vain for the patron in his studio increases the artist misery. through the study of elementary media the young artist has a basis that also includes the applied arts: he thereby mentally and economically arrives on a fertile path. (Typescript "lehr-system der klasse professor Willi Baumeister" [Teaching System of Professor Willi Baumeister's Class], April.6.1949, Baumeister Archive)

Many former students later recalled Baumeister's dictum "we don't paint pictures, we study". With it, whenever students in his class presented their works for discussion, he pointed explicitly to the character of the academy as an educational institution, not as a gallery. Baumeister also essentially never wanted to give an unambiguous answer to the question What is art? - at least none that could be expressed in one sentence.

Can Art be Taught?

Willi Baumeister openly held the view that art is neither teachable nor learnable: The teacher can create a broad horizon, provide stimulation, awaken enthusiasm, but the student must make the step to an "own invention" alone. (1948)

This attitude colored his pedagogy. Baumeister concentrated on a broad training that put elementary objectives into the foreground. Baumeister-student Klaus-Jürgen Fischer summarized it as follows:

He did not teach art, but the rules of art that are imperative for every talent. ... Everything ornamental, everything that is not an essential element of the picture, each form and color that fulfills no important ... function on the surface, that does not contribute to the unity of the total picture, is decorative. ... His "Theory of the Elements" was based on the simplicity of formulation of a pictorial problem and the limitation of its means, to avoid formal discrepancies, a lack of clarity, and overburdening, surface-destroying effects. This elementary theory ... was the guiding principle of his work. (from Kermer 1992)

Student Recollections

In later years many of Willi Baumeister's former students took the opportunity to write down their memories of him.

In the following commentaries, three things become particularly clear: first, Baumeister's ability to interact with students and not force a fixed doctrine on them, but still lead them firmly; second, the paternal relation without the drill atmosohere that young people remembered being typical after 1945; and third, his - for the academic situation of the time - unconventional instruction, for which most colleagues pushed Baumeister into an outsider role that he did not seek out but nonetheless accepted, because he knew he was on the right path with regard to artistic training.

- Klaus Bendixen: Decorative - That was Fatal" (1989)

- Heinz Bodamer: "Meditating with Forms an Colors Alone" (1987)

- Klaus Erler: "Energy Gradient and Artistic Impulse" (1986)

- Fia Ernst: "... like breathing in and out" (1990)

- Erich Fuchs: "You're not fooling me, just yourself" (1969)

- Peter Grau: "Eye for the Soloists" (1989)

- Herbert W. Kapitzki: "Beyond Art Studies" (1989)

- Eduard Micus: "New Beginning in All Directions" (1989)

- Fritz Seitz: "Guarantee for Something Very Different" (1979)

- Fritz Seitz: Funeral Oration (1955)

- Gerhard Uhlig: "Art Theory Requires Objectivity" (1986)

Up to Exhaustion

As in his Frankfurt period Willi Baumeister had to find now, too, that teaching- as Adolf Hölzel had warned him - was no unfettered bliss. After the privation-rich war years, his strength was rapidly consumed. On January 5, 1949 he wrote in the diary: "The entries are sparse because there is not enough time and the day demands too much. And three weeks later he added:" Dr. Domnick urgently recommends a break from work and stress. A stay at Bad Ditzenbach is being considered - a health-spa cure that he began a few days later.

" Baumeister made it easy for neither himself nor others"

... wrote Wolfgang Kermer in his 1992 book The Creative Angle: Willi Baumeister's Pedagogical Activity. Kermer deals at length with all facets of the Baumeisterian teachings within and outside of the academy - and with the dispute with Sedlmayr about the relation of representational and non-representational painting in the Darmstadt Dialogue in 1950, his disagreements with Rector Hermann Brachert, his pedagogical building blocks, and much more. He continues:

He was averse to every schematizing mode. He was an opponent of the status quo. His rejection of a pedagogy [based on] protection and adaptation, the manner in which he approached those studying in his class, was beyond the comprehension of those who saw the academy and instruction ... in unison with artistic action.

Baumeister practiced not only his pedagogy in this fashion. Such was his art - and his life as well. This book is recommended to all those for whom Baumeister was and is more than just an artist.