Willi Baumeister’s drawing oeuvre of around 2,300 known leaves is just as extensive as the painting oeuvre. In this case, only a few early drawings survive, since he himself later destroyed many works.

In contrast to many other artists, Baumeister’s surviving drawings are only rarely to be understood as a concrete preliminary stage to a painting. His preparatory sketch was typically produced on the canvas or cardboard itself. Preliminary sketches also would have contradicted Baumeister’s concept of a continuous creative process during the production of a work. Some drawings, on the other hand, are often to be understood as a memory or demonstration sketch of a completed course of painting. In any case, most of Baumeister’s drawings are – as he himself put it in 1942 – to be entirely set on the place a completed picture.

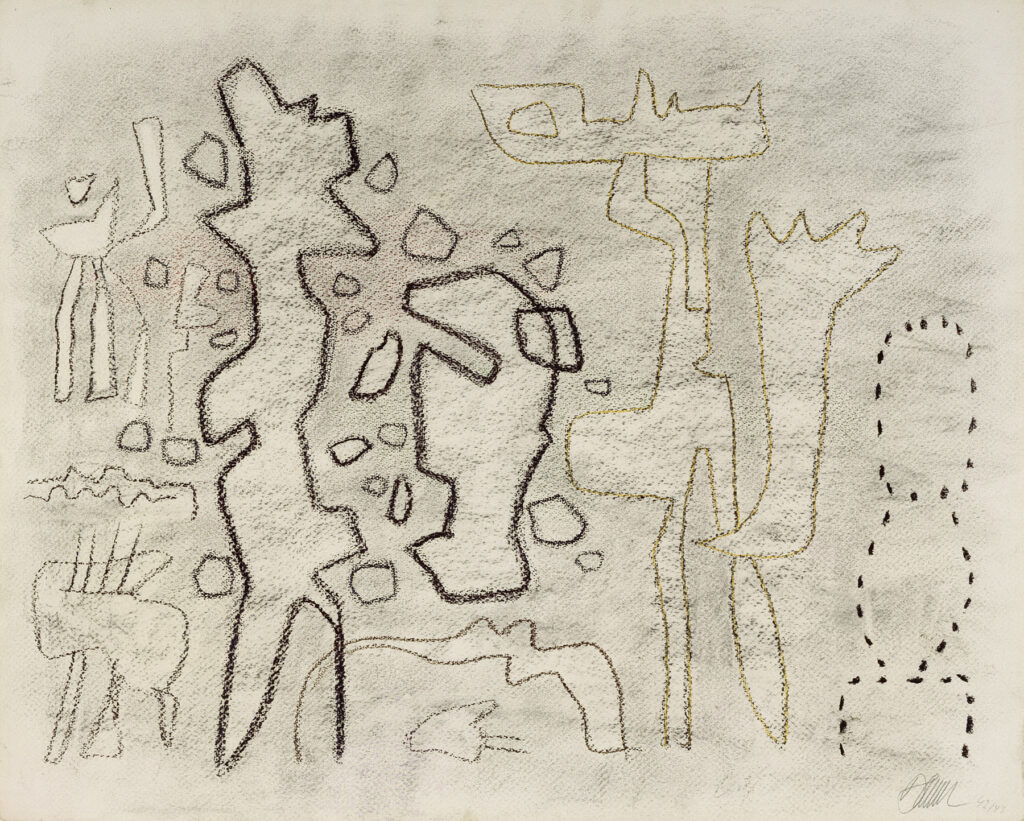

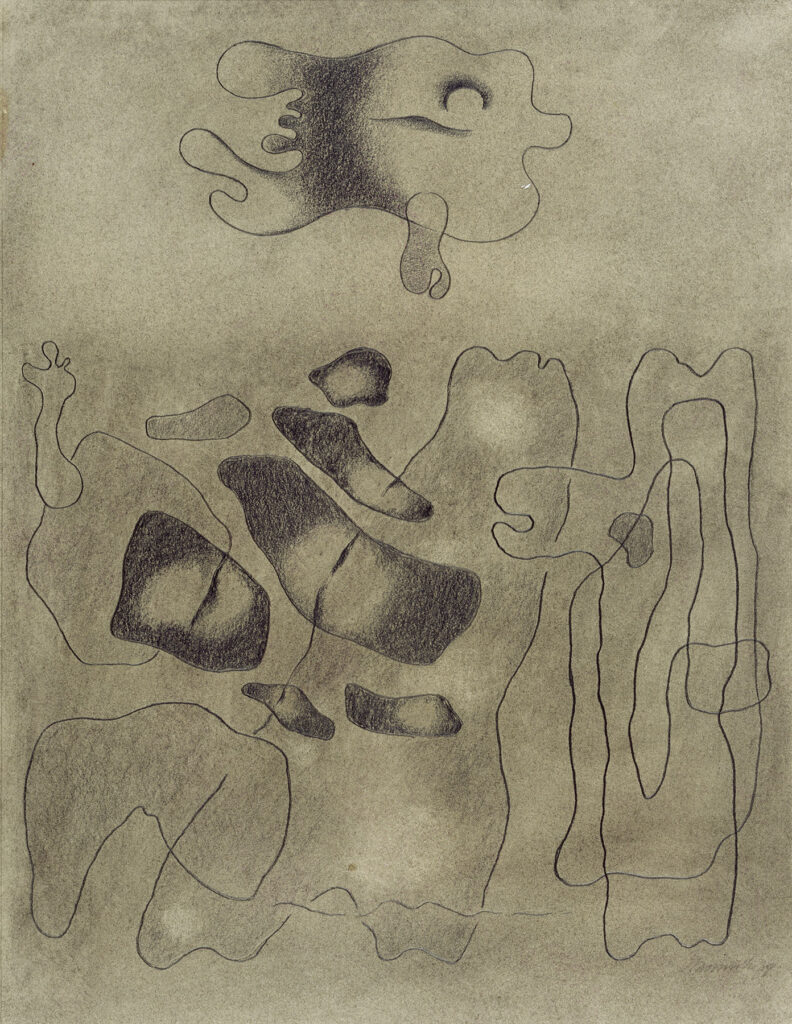

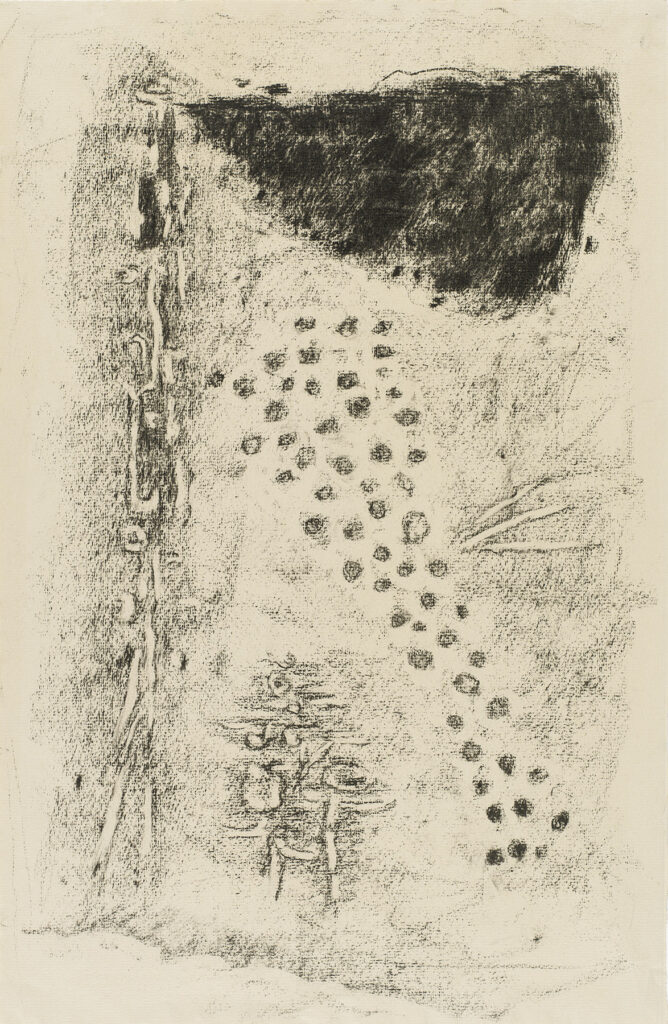

In terms of technique, drawing with charcoal, crayon, or pencil predominate, whereas pastel, colored pencil, and gouache are more seldom. Correspondingly, the number of monochrome works is distinctly greater than colored ones – particularly in the years up to 1945. Here the conscious use of colored paper should not be overlooked.

Baumeister’s artistic development as a painter, which often took place alongside changes in the use of painting media, can also typically be seen in the drawn work itself. Interesting in this case is that he now occasionally had to translate as, for instance, with the Wall Pictures’ (1919–24) relief structures and materiality, which he partially transmitted into drawing as collage.

Later, frottage and other rubbing techniques as well as blurring offered him the chance to translate color values from paintings into graphic works.

For Baumeister, painting and drawing held equal importance within artistic work. He once referred to his drawings as his greatest treasure. Even so, there were phases in which he turned more strongly to drawing and graphic works: during the professorship in Frankfurt and the last war years before 1945. In the former, he had less time for work at the easel than before; in the latter case, the lack of canvas and oil paint forced Baumeister to switch to other techniques.

Ways to Form

At the beginning of Willi Baumeister’s artistic development between 1911 and 1914, numerous studies of Figures in the Landscape appeared that clarify his interest in Cézanne. The spatial element that was still present at this time largely disappeared by 1918.

The drawings produced between 1919 and around 1926 reveal the same principles as the Wall Pictures and the subsequent machine pictures: geometric compositions with the ongoing concern to depict the motif through line and plane, rather than through corporeality. A few experiments in the direction of the nonrepresentational accompanied the figural pictures. On the other hand, to the degree he could Baumeister later destroyed works that showed a more plastic approach to the human figure.

From Construction to Movement

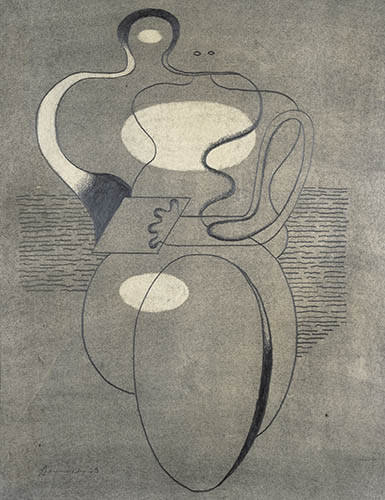

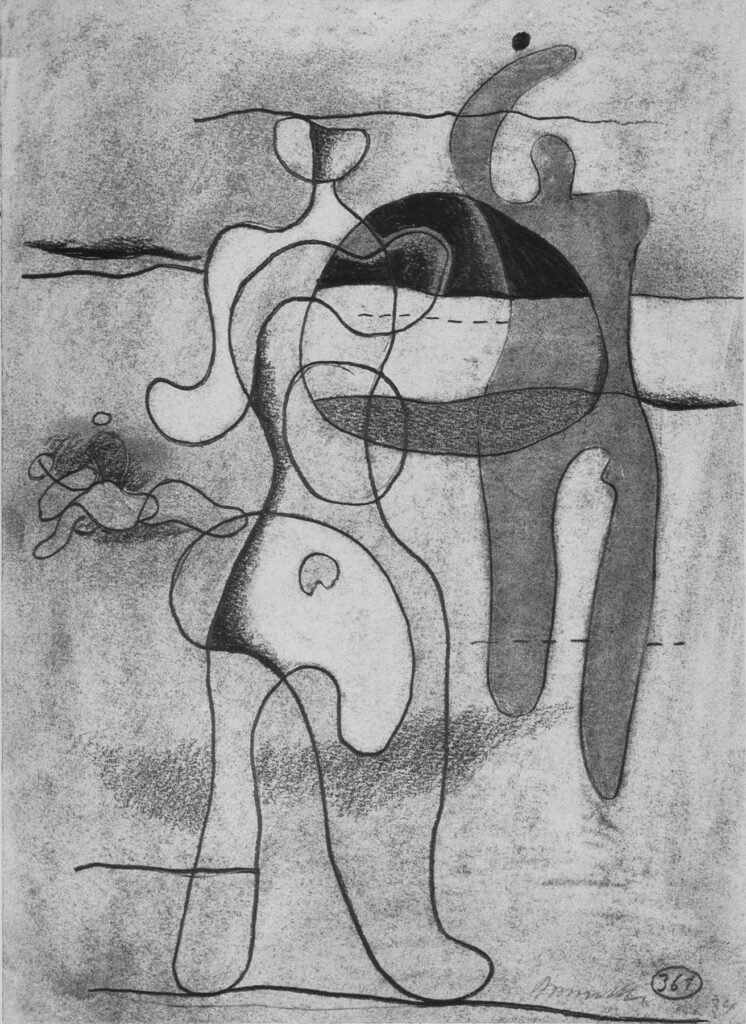

Analogous to the development in his painting, beginning in 1926 Baumeister’s drawings gradually overcame the constructivist lack of motion in which his figures had remained static. This becomes formally and thematically equally clear. Until long into the 1930s, the sports pictures determine his works. As a formal analogy to the movement of the handball and tennis players, gymnasts, runners, and jumpers, the lines now grow more fluid and organic, the compositions more active, and the tonal values more nuanced.

At the same time, the degree of abstraction remained high, a quality that becomes especially clear in the drawings of those years in which Baumeister could reduce form to the essential – up to more recent experiments that almost completely repress the human figure behind the structuring of planes. In his drawings he now turned the development of formal media toward a livelier manner of organization with blurring, shading, and the use of colored paper.

The Unknown Clears the Way for Itself

After his brusque dismissal from service at the Frankfurt Art School in 1933, the themes and forms of his art gradually changed. But even years later, a few drawings still reflected the earlier formal basis. Nevertheless, the forced break in his artistic activities accelerated the production of graphic works, particularly because beginning in 1941 oil paint and canvas were barely still available. The 1941 ban on painting and exhibiting were another part in this.

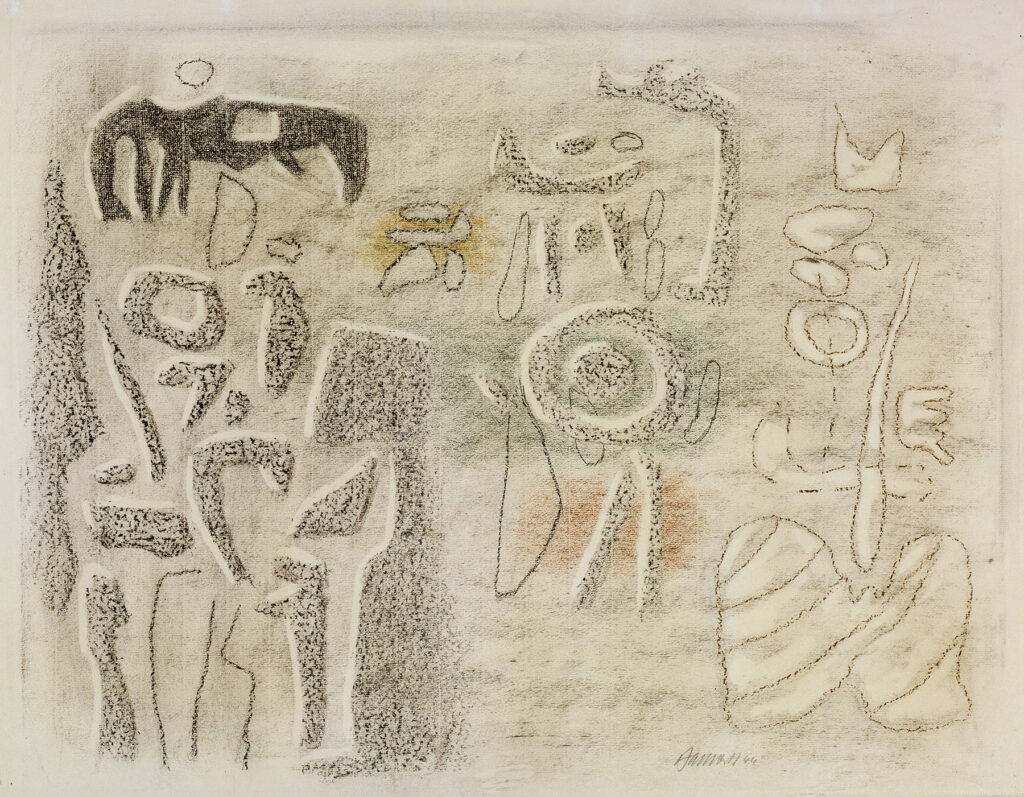

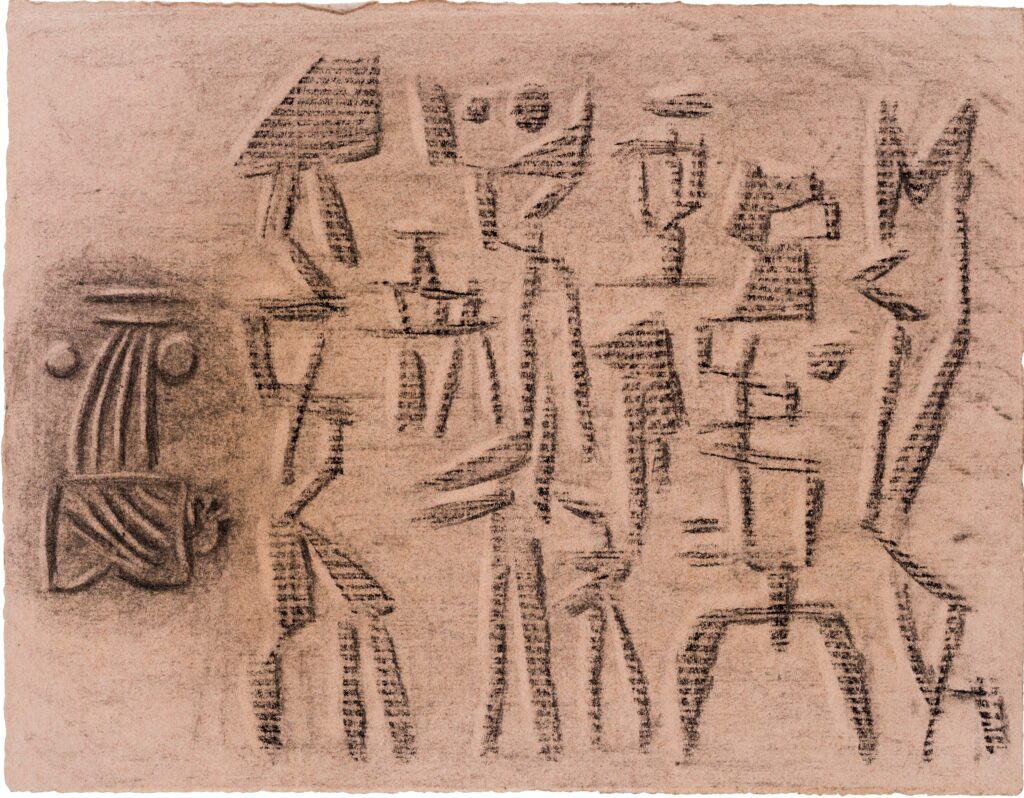

Essential for the development of his drawings up to 1945 was Baumeister’s engagement with ancient texts and with archaeology, which increasingly fascinated him and ultimately precipitated his manuscript on “The Unknown in Art” (Das Unbekannt in der Kunst), published in 1947. The thematic realm of the works thus often referred to Africa but in particular, to scenes from the Old Testament.

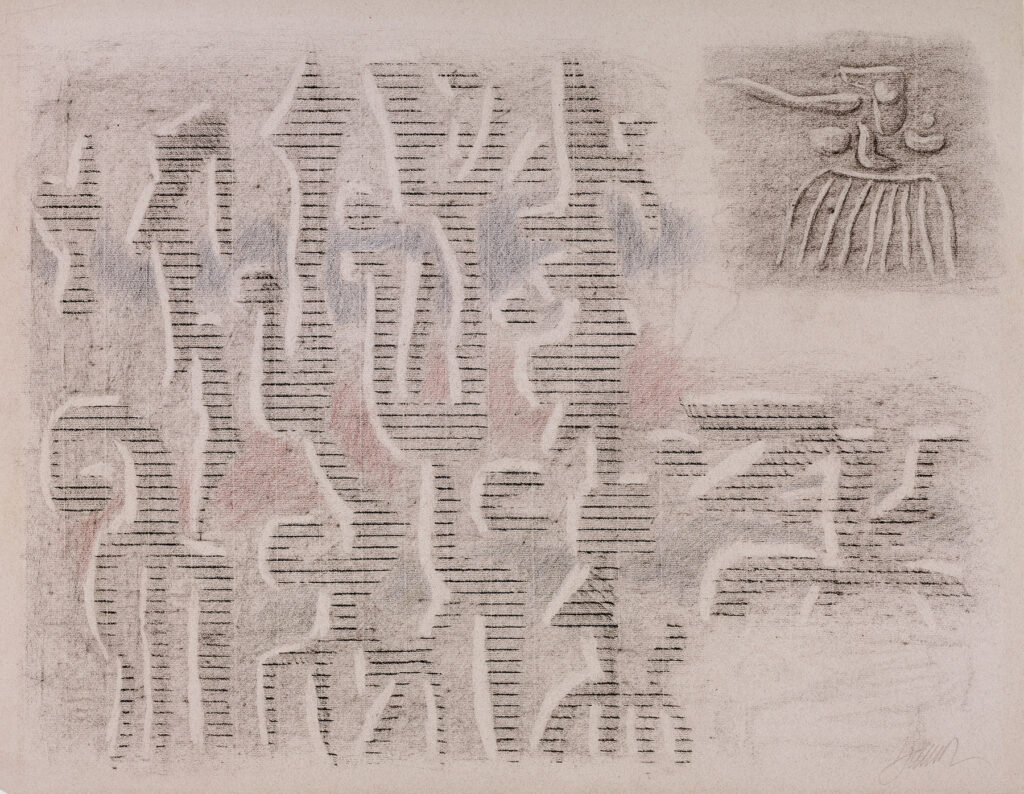

This is reflected in the extensive illustration series, such as those of the “Gilgamesh” epic (1943) with over 200 drawings, the “Book of Esther” (1943, ca. 100 leaves), and “Saul” (1943). With these relief-like, emphatically planar, and largely linear figurations, Baumeister drew a direct formal connection to works from around 1930–35. In their content, however, the profound and beleaguering motifs refer to the special circumstances of the time. There is little correspondence to these illustrations in his paintings.

The relation is comparatively different in the multi-figured Africa pictures, which also found correlation in a few charcoal drawings around 1941. Furthermore, the origin of life and its metamorphoses, with which Baumeister also approached the elemental between 1938 and 1942 are likewise present not only in the paintings, but also in numerous Eidos drawings.

The planar reference is always the determining factor in the works. The emphatic contouring generated a relief-like construction, whereas blurring led to semi-painterly effects.

Interacting with Painting

After the war’s end in 1945 and the assumption of his professorship in Stuttgart in 1946, his drawing production gradually decreased beginning in 1947.

But in many cases the prevailing themes in those years remained overshadowed by the approaching war years: primordial figures and giants, figure walls and prototypes as well as many relief-like figurations. In technical terms, Baumeister initially remained committed to proven principles. Blurring and rubbing techniques, colored paper, heavy contours, and an economical use of color distinguish the works. As in his painting, though, the palette at least occasionally brightened up and some compositions became lighter, as the drawings with harps and sun figures and the use of rubbing techniques reveal.

In the last years Willi Baumeister increasingly turned to color and a larger format in his painting. Both developments appear in the drawings as well.

In numerous Montaru motifs (1954) with smaller planes in primary colors that gather around a large dark center, or various yellow-colored Safer drawings (1953), he also sought an adequate expression in the art of drawing. This especially goes for the serigraphs of the late period.

From Drawing to the Sign-like

Overall, Baumeister’s notion of a picture as a sign clearly comes to light in his drawings and ultimately throughout his entire production. For Willi Baumeister, the calligraphic moment that distinguished drawing from painting was an important key to art. Especially in difficult times, in which hardly any options for pictorial expression were available to him, he drove the analogy between ‘drawing’ (German: Zeichnen) and the ‘sign’ (German: Zeichen) to a climax in the Biblical illustration series. Even in other phases of his efforts, drawing always offered a chance, through the concentration of means, to forge ahead to the regularities of art and appearances.