Even though Baumeister had been imposed with an exhibition ban, his work and its development in the period between 1940 and the end of World War II were diverse. The African sculpture in which he saw universal images of human existence was reflected in an increasingly strong colorfulness. Wall forms and positive-negative structures also dominated the work. Moreover, great drawing cycles emerged alongside the paintings.

Paraphrases of Africa

Willi Baumeister began collecting nonwestern and prehistoric art in the 1920s. Unlike the expressionists, Baumeister did not use African art as a direct model, but saw a generally-valid, timeless artistic message in it: the mythical, rhythmic, earthbound, allegorical, and thus – so to speak – the sacred as well. Just as he had in connection with the rock paintings ten years earlier, Baumeister perceived in African art and culture the stimulating power, ornamental structures, and color tones that he translated into his own sense of form.

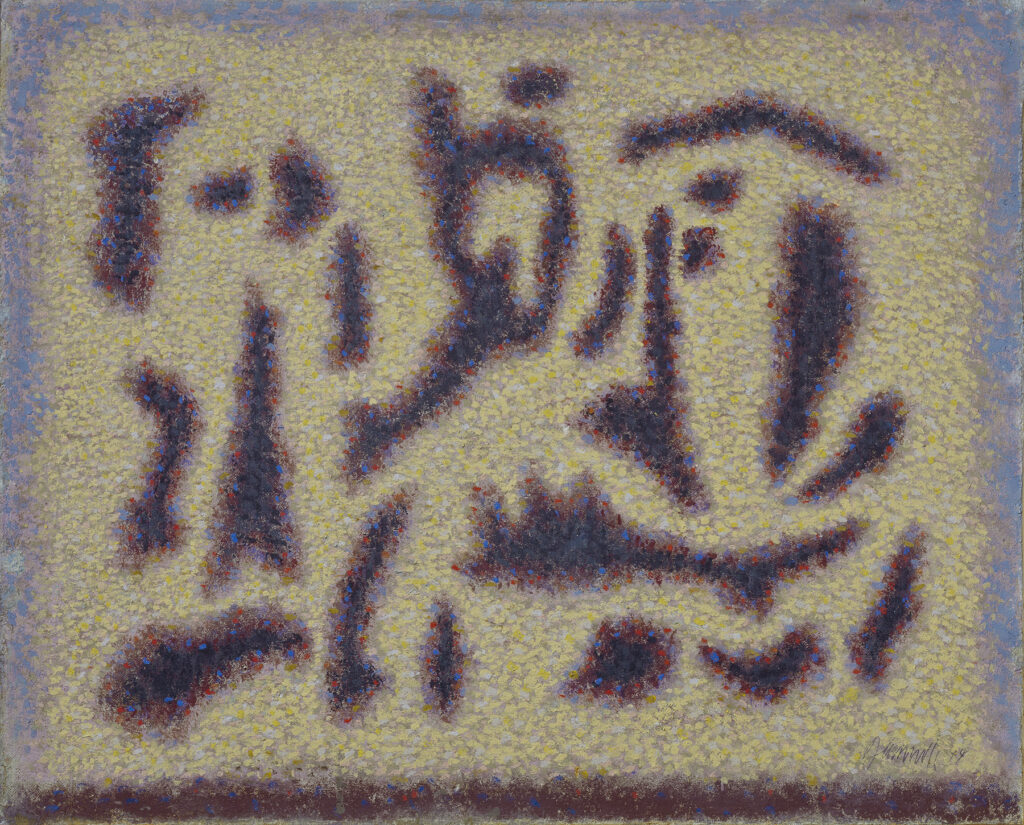

This exploration is reflected in an expansive body of works produced over an extended period between 1942 and 1955. Baumeister did not obscure these references, but gave his pictures titles such as “Africa with Yellow Horizon” (1942), “African (Dahomey)” (1942), “Drumbeat” (1942), and “Owambo” (1944). Formally they distinguish themselves strongly from the Eidos compositions. Whereas flowing and floating forms prevail there during the same period, more angular figures in a fixed, relief-like texture appear in the Africa pictures. As such, Baumeister used artistic means to respond to, for instance, the staccato of the African dance and give it new form.

Even so, he directly resumed the painterly phase that took on flowing forms around 1930. Among a series of paintings that resemble figural landscapes belongs Dedicated to Jacques Callot of 1941.

Epic and Relief as Tenses

The latent threat to his existence posed by the outbreak of war and painting and exhibition prohibition, which culminated in the destruction of the residence and studio by bombs, also found resonance in the pictures. In this case, he synthesized personal experiences and the content of ancient epics. For Baumeister, the Gilgamesh epic in particular became the ultimate parable of human life, of the struggle with and victory over danger, of the attempt to escape defeat through eternal life, but also of the stoic calm to come to terms with his fate. Other ancient stories and motifs from Mesopotamian, Greek, and Biblical sources also served Baumeister as exemplary inspiration for his work.

Thus from 1942 until long after 1945, numerous paintings emerged with titles referring to archaic worlds such as “Gilgamesh and Enkidu” (1943), “Ur-Nugal” (1944), “Archaic Dialogue” (1944), and a few others. Baumeister linked the literary models with the art of pre- and early history so that the figures resembled stone-age monuments, scratch drawings and cave pictures, and especially abstract reliefs that project beyond the painting surface in an impasto of color, synthetic resin, and putty.

Whereas the painterly aspect predominated in the Africa and Eidos series, Baumeister now highlighted the sculptural appearance of his figures. Through the block-like treatment of their, in a sense, positively protruding picture elements, he simultaneously achieved a negative layer that in turn also possessed an intrinsic value. This generated a continual movement of vision that gave the work of art a multifaceted quality.

Multi-dimensionality and the Hope for Redemption

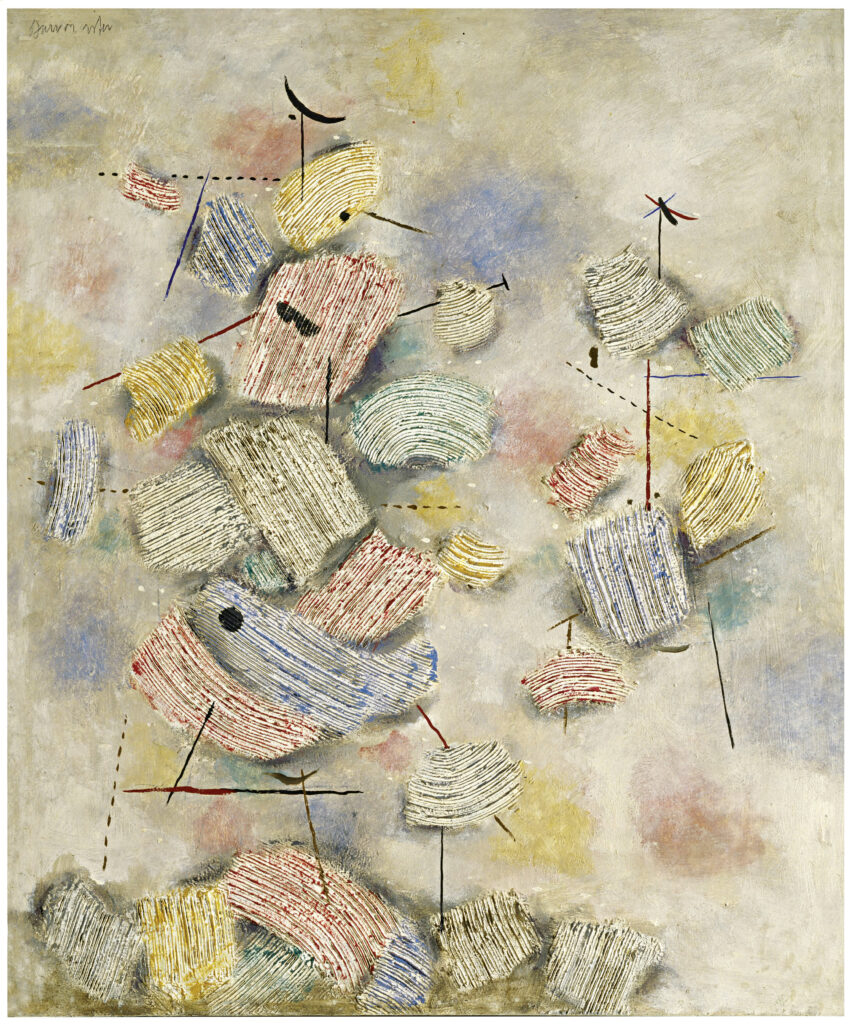

Unambiguous picture content had never corresponded to Baumeister’s artistic concerns and did so even less in this phase. Similarly, in several works that he called perforations, brown or blue-gray forms appear that can be read both positively and negatively. Relief and perforation are essentially two different means of approaching the same theme. Typical of this phase’s multi-dimensionality is the title of another painting from 1942: Not Yet Deciphered.

The painting “Remnants of Memory” (1944), which resembles an archaic type of writing, is conceived in a relief-like manner similar to Jurassic and Gilgamesh, but is more strongly reduced in the direction of line drawing. As a result it seems – like Stripe Composition on Purple of the same year – lighter and less threatening. This quality characterizes other works from 1944 such as the Sun Figures that, with their bright cheerfulness, can be read as a premonition of, or even an entreaty for, the end of war and thus of redemption.

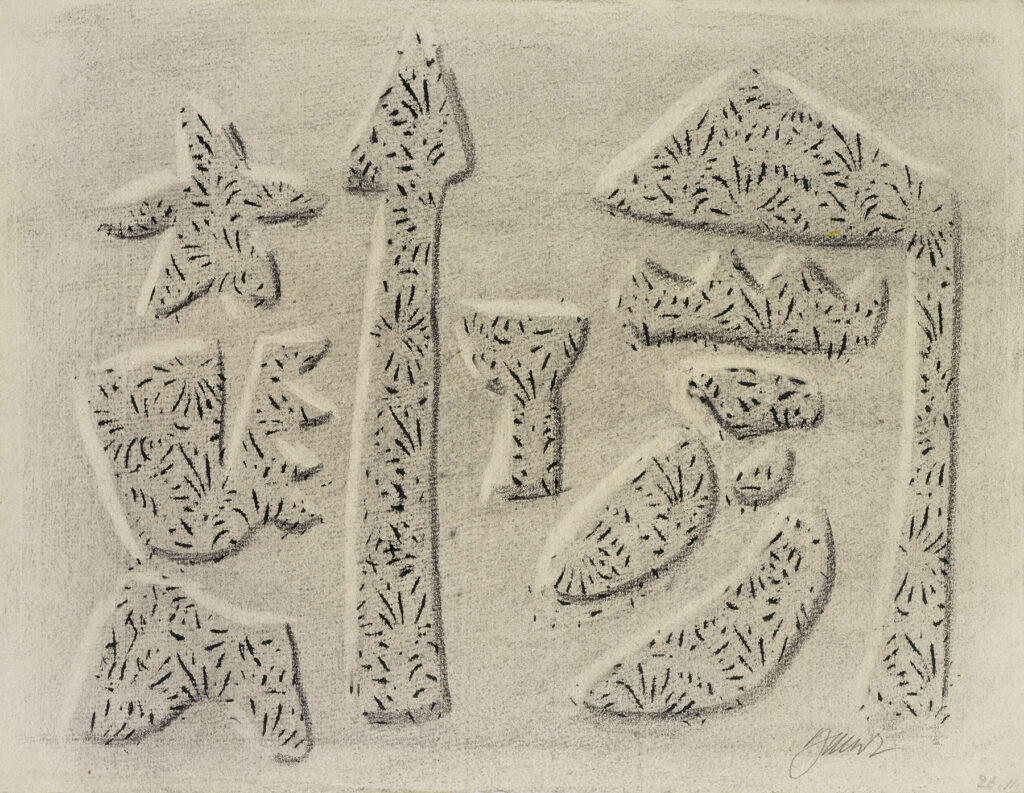

He stressed this intention by using the new combing technique with whose help he gave individual picture components a surface that is lively and bursting with light. He used this technique, with which he now also gave surfaces movement and direction, long into the 1950s. In the drawings it more frequently appears in the form of a frottage technique.

Baumeister’s drawings are discussed as an individual aspect.

Toward the end of the war Baumeister increasingly turned to drawing. On the one hand, the turn came about due to the lack of oil paint and canvas and, on the other hand, it offered him the opportunity to quickly and directly realize his notion of an elemental art. To him the character of letters also seemed better articulated on paper than in large format. As discussed above, the figures of mythological epics appeared to him, like those of the Old Testament, as ciphers of a world that was no longer understood. In several drawn illustration series he explored this theme on a broad scale, beginning with Gyges (Herodot) and Gilgamesh and proceeding onto the books Esther and Saul and the story of Salome. All of these epics thematize domination, resistance, and redemption. The reference to National Socialism is clear and becomes even more apparent when one notices that he translated the cycles into lithograph shortly after 1945 in order to make them – after years of isolation – accessible to a broader audience.

In over 500 leaves (!) Baumeister gave free reign to all his abilities. Particularly current among them were emphatically relief-like compositions, as in Gilgamesh VIII and IX, or highly symbolic and extremely contrasty figures, as in the leaf Esther XX. In comparison the cycles seem like a Baumeister legacy, since one finds in them depictions that recall figures from the 1920s, the Runner (Gilgamesh IX), Eidos figures, and ideograms (Esther XVI) from the 1930s, or the Africa pictures of 1942.

Undoubtedly, the threat posed to the painterly oeuvre by bombs and by the Nazi iconoclasts led to a richness of creativity within just a few months – a richness that would continue uninterrupted after the war’s end from 1945 to 1950.