In his last work phase innumerable magical fantasy-beings emerge that no longer derive from the archaic world of earlier years. With them, Willi Baumeister developed his characteristic form of abstraction further and again found new direction. In many paintings as in serigraphs, with which he was intensely occupied, he again took up several themes and formal problems from his earlier work. In this way Baumeister’s work from 1950 to 1955 gained many facets as seldom before.

Retrospective and Development

Although Baumeister was just in his early 60s, the artist’s mature work stands out like a legacy. After 1950 he synthesized together many currents, developments, and ideas from his own oeuvre in new picture creations. An important reason for this was that, in new artistic freedom and in connection with the atmosphere of a new beginning among artists in Germany and Europe, he re-examined and newly interpreted some things to confirm his own standpoint and role as a representative of abstract art.

The Wall motif, the relief and Non-objectivity had preoccupied him since 1919, Archaic and Foreign Cultures, Symbol and Sign since 1931, Metamorphosis and Figure Landscapes likewise since the early 1930s, and Glazes since 1935. These all – like the themes Ideogram (begin 1936), Africa (begin 1942) and Gilgamesh (begin 1943) – now play a central role again. This is also the case for the combing and rubbing techniques (both begin 1943–44) and the use of sand ground beginning in 1920.

The examples show Baumeister’s in part free references to his own work. With them he particularly explored the new technique of the silkscreen print – Serigraph – which he convincingly knew to use for his purposes.

The translation effort is particularly evident in “Safer 5” (1954) and the Han‑i pictures of 1955 with their clear references to cave-painting or ideograms reminiscent of Asian art. Both were key motifs of Baumeister’s following his dismissal from the Frankfurt professorship in 1933. The comparatively severe axial quality in the Han‑i works, however, also reveals references to the Wall Pictures of 1920 to 1924. Magic Rupestre (1953) recalls the glaze pictures of 1941, but its forceful linear quality is hardly imaginable without the drawing cycles of 1943.

Step-by-Step into the Worlds of the Unfathomable

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Baumeister strode step-by-step into the deep – to the beginning of creation, of artistic form, of human impulses. It is not by chance that the title of his 1947 book is “Das Unbekannte in der Kunst” (The Unknown in Art). For him this unknown had countless faces and styles. And it preoccupied him from then on! Between 1935 and 1945 he even gave names to the unknown: Runner, Chumbaba, Africa […] he gave it forms, colors, movements, and sounds.

The Sea – Night – Phantoms – Goblins became essential themes of his pictures beginning in 1950. In various ways they all deal with primordial situations and unknown energies. Even so, Baumeister’s works do not evoke feelings of oppressiveness; they are not motifs of fear, but at most of the incomprehensible, which could also be fascinating. For him the sea and the night (Seaweed, 1950 – Nocturno, 1953) were creative elements. Phantoms and goblins (French: Lutins) appeared as welcome companions.

The Metamorphoses were a second step into the world of the unknown. Baumeister already hit upon this motif in 1938–39 with the Eidos pictures which at the same time resulted in the Ideograms. But he now brought it to a finale when he combined growth and calligraphy. He removed all traces of the figurative and retained only sign-like tissue structures and nets that recall neuroplexuses. The elements of other abstract pictures (e. g. Figure in Motion, 1952) are reminiscent of cave paintings, but especially of bacteria or sperm threads that gradually join more complex structures, but still seek a fixed order.

Black and White Cosmos

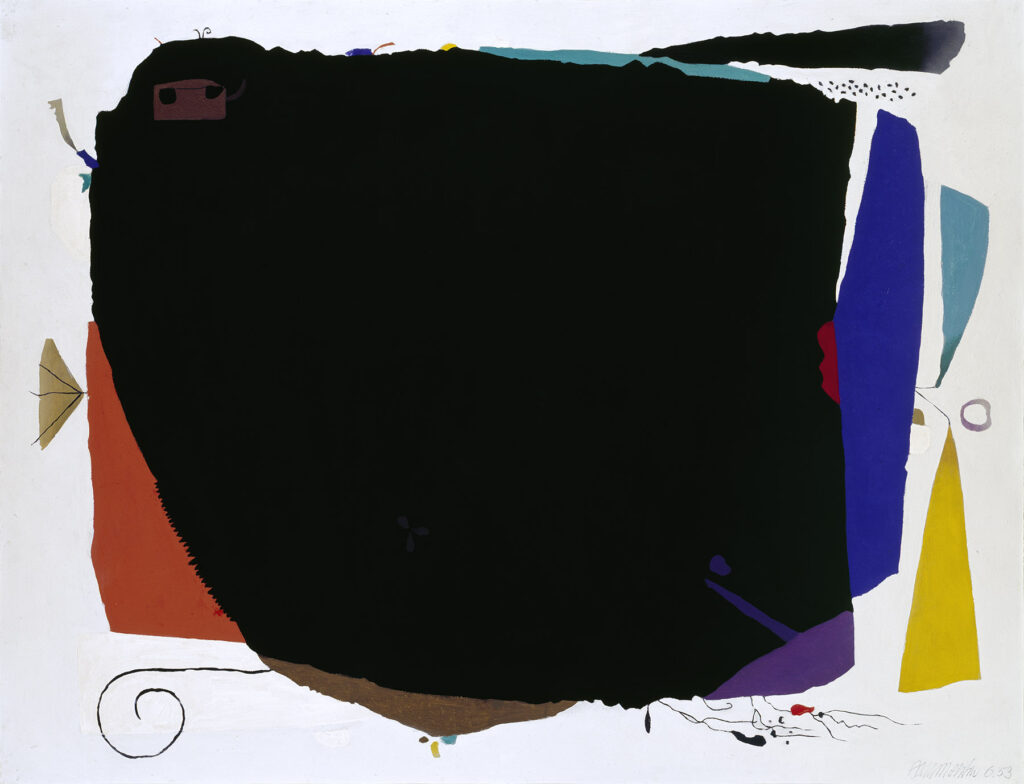

Baumeister introduced a completely new form of the idea of positive and negative, which concerned him for 20 years, with the Montaru and Monturi series produced between 1953 and 1955 and respectively comprised of 56 and 16 mostly large-format works. With this last large work complex, to which the ARU pictures also belong, Baumeister reentered a realm that he had last tread in the 1930s: that of the large black forms.

The phantoms of 1952 had already suggested it: the central figure – identifiable as such only by insect-like legs and antennae and tiny eyeholes – began to gradually expand over the picture surface and cover everything. The Montarus appear as cosmic black holes: threateningly and magically attracting at the same time. One can hardly break away from their fascination especially since Baumeister by no means relinquished the bright coloration of his other works, but added strong color contrasts to the edges of the black forms. Thus creatures like black angels from an unknown sphere emerged – attracting, without evoking fear.

Similarly counterbalanced like the small colored and large black forms, the concurrently produced Monturi pictures also relate to the Montaru. Compositionally comparable, they, however, are dominated by a large white form. With these two work groups Baumeister mediated the dark and light sides of the cosmos with a black and a white energy field, with energy that absorbs everything and that – like the sun – releases everything.

Sonorous Names

As Baumeister journeyed further into an unfathomable world, traditional picture titles longer played a role. In their place he often used melodious names that underscored the intention of the work. In the case of the two previous series, the black pictures bear the dark tone ‑u, whereas the titles of the white pictures have the bright-sound ending ‑i . This onomatopoeia-painting recurs in other works such as Nocturno, Bluxao, and Kessaua and, finally, in the last large work-complex ARU.

Last Works

ARU continued the Montaru idea. Baumeister returned to a more strongly figurative mode of depiction and lent the black form, so to speak, arms and legs with which it could even more strongly reach out into the picture surface (Aru 2 , 1955). He partially reduced the color contrasts to their complete dissolution (ARU Dark Blue, 1955). But here, too, Baumeister placed a sign of hope, as in “Aru with Yellow” (1955) whose bright color values already occupy half the picture and appear to increasingly displace the black.

Despite Baumeister’s use of so much black, we cannot presume him a difficult character. He was a lifelong optimist, in human and in artistic terms. Many works, produced along with the Montaru and ARU pictures, show his work from the cheerful, positive side — #as it already was at the end of World War II. That he almost completely renounced heavy earth colors already in this work phase provides an indication. With their floating, colorful elements, paintings such as “Hommage Jérôme Bosch” (1953), “White Butterfly” (Weisser Schmetterling) (1955), or “Bluxao” (1955) continue to exhibit the lightness of many works beginning in 1944.

As in almost all his production phases, his work was now also oriented toward the concept of thesis and antithesis. As always he played with a formal problem or a multifaceted theme, found various approaches and answers, never stopped short, was never satisfied. He left some things behind on this path, only to take them up again at a later date. He restlessly strove to give form to the unfathomable. How close he felt to “The Unknown in Art” in the late summer of 1955 is not known. The works of his last phase of production reveal, as do many of his statements from those last years, that he was probably closer than ever before.