At the end of the 1910s Willi Baumeister discovered the theater as another field for his artistic activity. Up to now Baumeister had been intensely occupied with painting. He increasingly distanced himself from the two-dimensional surface. His constructivist paintings of this time frequently manifest relief-like elements. As such, individual color planes or formal elements emerge haptically via the application of plaster or pieces of plywood.

The relationship between plane, space, and architecture represented an important issue for him: Baumeister produced his so-called Wall Pictures during this time. These wall works, which project into space via relief structures, were a result of this activity. It is thus not surprising that he was attracted to working in the theater, since it concerns giving form to the clearly defined, three-dimensional space of the stage.

Setting Out Toward a ‘New’ Stage

Since the end of the 19th century a development to renew the theater began to emerge. The need for change and a start in a new world increased after World War I. The younger generation perceived the academicism that had determined the European and Russian stages as in urgent need of updating. The narrow objectivity of the naturalistic stage had to be replaced. Many, later very famous, directors such as Konstantin Sergejewitsch Stanislawski, Wsewolod Emiljewitsch Meyerhold and Max Reinhardt saw the potential to activate the stage in the fine artist and particularly in the painter. Interestingly enough, right at the end of the 1910s and early 1920s, a completely new stage scene emerged that was indeed given shape by painters. The shift in viewing habits that had taken place in the fine arts at the turn of the century also found manifestation on the stage. The stage became a venue for new artistic forms.

Baumeister’s Designs as Stage Production Contribution

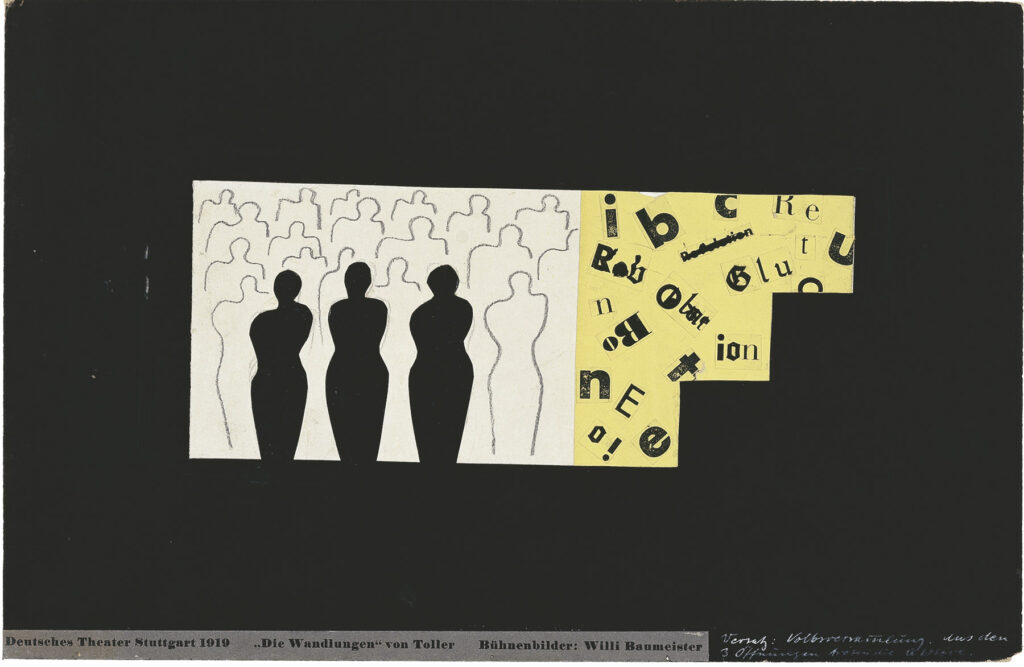

For plays such as Georg Kaiser’s Gas (1919) or Ernst Toller’s Die Wandlung (1920) Baumeister developed the simplest constructions for the stage, since for him it was not a matter of designing a naturalistic space and illustrating the piece, but of having the stage design actively contribute to the production. These first designs were implemented on the stage of the private German theater in Stuttgart. They easily join the avant-garde works by Russian artists such as Alexandra Exter and Ljubow Popowa and Alexander Wesnin.

Many years later, on February 26, 1950, Baumeister wrote Egon Vietta (dramaturge and critic), for whom he had produced stage designs in the 1950s:

decoration, lighting, and costumes amplify the action on the stage and double the artistic value of the theater piece offered earlier. — since the media of stage-design derive from its elements, they do not remain in the function as a

background, merely illustratively (- naturalistically -) derived — but gain an inherent power. they accompany more the action on the stage than they simply play a derivative role.“

Interesting is that this statement can already be applied to the first of his stage designs and that his viewpoint can be traced throughout his entire stage work.

The Meaning of Color

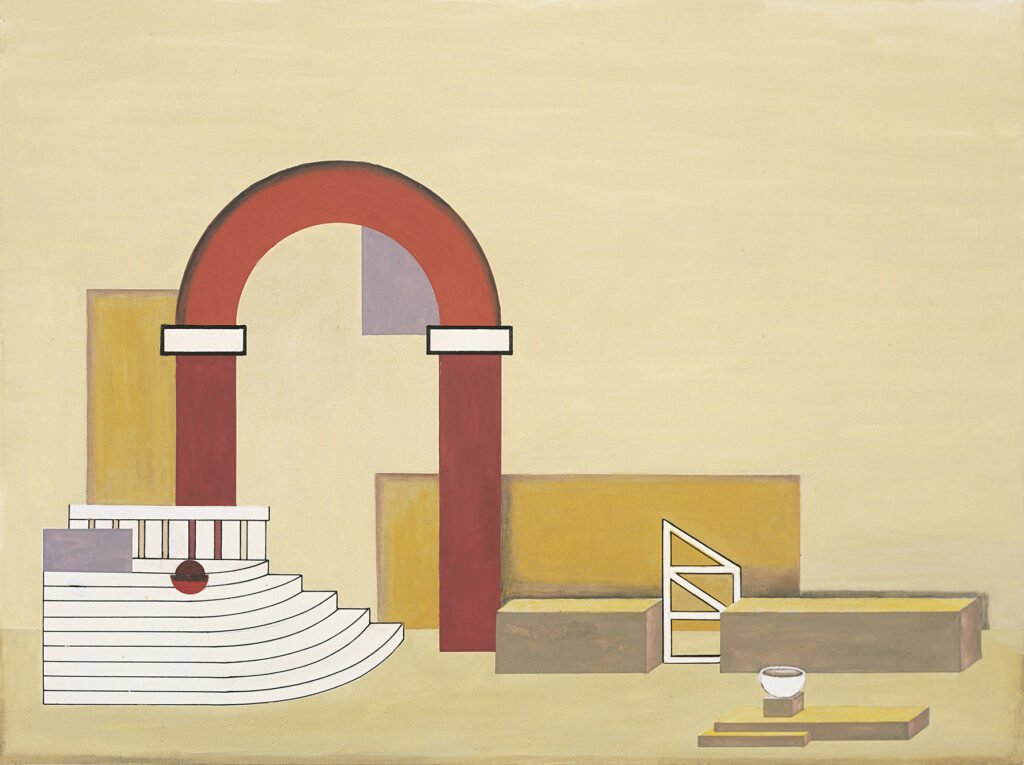

In 1926 Baumeister produced the stage design for Georg Friedrich Händel’s opera Ariodante at the Landestheater in Stuttgart: it presented a clear stage space in which a balanced relationship existed between the space, singers, and chorus. He also stressed precisely used color planes that, through a new lighting technique, could be specially worked out. Specific colors were assigned to each of the individual figures. The hero and heroine appeared in white and lemon yellow, the red in king. In this he worked out an exact chromatic scale and values for the soloists and the chorus.

During his teaching activity in Frankfurt from 1928 to 1933 he produced two other stage designs for the Südwestdeutscher Rundfunk (Southwest German Radio) in Frankfurt. During the National Socialists’ twelve-year reign he could not — as ‘degenerate’ artist — work for the theater.

New Approaches After 1945

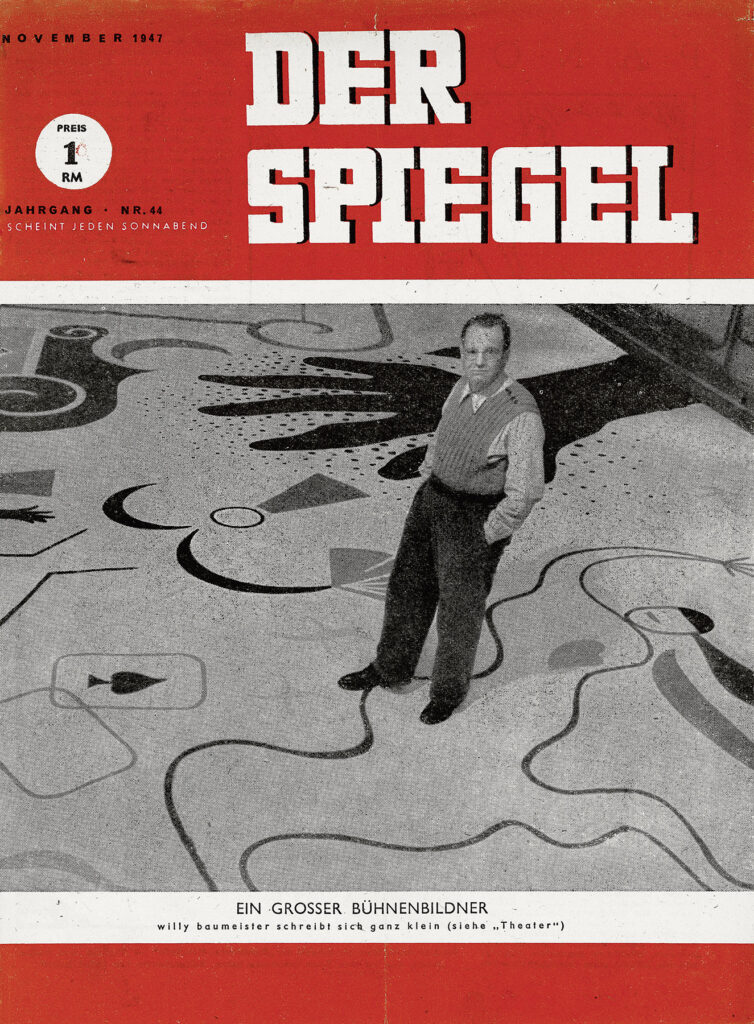

But already in 1947 he produced — again for the Southwest German Radio — his first postwar stage design. In October of that year the premiere of the ballet ‘Liebeszauber’ (Love Spell) set to music by Manuel de Falla took place in Stuttgart. The stage design was a sensation — with it Baumeister landed on the cover of the magazine Spiegel. The pre-World War II constructivist-style scenery was dissolved through free, partially playful forms that opened up a perceptive space for the spectator that he could fill through his own imagination.

In the years prior to his death in 1955, he produced seven additional stage designs. Under his supervision a number of his students created stage designs in 1949 for Ullrich Klein-Ellersdorf’s ‘Franziskuslegende’ (Franciscan Legend).

The Task of the Stage Design

In 1953 Baumeister stated in the journal ‘das neue forum 6’:

Stage design is certainly also about serving a purpose, though not in an illustrative fashion. It is reduced to the unavoidably necessary. The active stage design is not “complementarily” illustrative. Corresponding to this procedure, the stage design, with all its media (word, gesture, costume, stage design, possibly music) is indeed initially divided into its individual media — it purely allows these elements to have their direct, elementary effect and first achieves the strongest synthesis of an art form in the final “coming together” through a will to completion.“

As Baumeister saw it, the task of the stage design consisted of the fact that it did not completely clarify or explain everything. This meant that the spatial and architectural, chromatic and lighting media and the stage’s mobile components must mutually allow themselves sufficient room to develop and should simultaneously appear abstracting.

Baumeister’s formal language on the stage changed — just as it did in his painting. Even so, he remained loyal to his belief that stage design should be part of the total stage experience.

Overview of Baumeister’s Designs for the Stage

This overview lists all Willi Baumeister’s drafts for theater, ballet, and opera. You will find a more extensive discussion of Baumeister’s notion of a modern relation of stage design and production on a separate page.

1919 Stuttgart

Georg Kaiser, “Gas” (drama)

1920 Stuttgart

Ernst Toller, “Die Wandlung” (The Change) (drama)

1920 Stuttgart

Herbert Kranz, “Freiheit” (Freedom) (drama)

Stuttgart 1921

William Shakespeare, “Macbeth” (drama)

between 1921 and 1926 Stuttgart

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, “Faust” (Part I) (drama)

1926 Stuttgart

Georg Friedrich Händel, “Ariodante” (opera)

1927 Stuttgart

Hans Gustav Elsas, “Das Klagelied” (The Lament) (drama)

1931 Frankfurt a.M.

Darius Milhaud, “Theseus” (short opera)

before 1933 Frankfurt a.M.

Carlo Goldoni, “Harlekin, Diener zweier Herren” (Servant of Two Masters) (drama)

circa 1947 Stuttgart

Calderòn de la Barca, “Dame Kobold”, (Lady Kobold) (drama), Theater der Jugend, Rotebühlstraße

1947 Stuttgart

Manuel de Falla, “Liebeszauber” (Love Spell) (ballet)

1948 Stuttgart

Paul J. Müller, “Einmal Hölle und zurück” (The Road To Hell and Back) (ballet)

1949 Wandertheater

Ullrich Klein-Ellersdorf, “Eine Franziskuslegende” (A Franciscan Legend) (drama), stage design by students of Willi Baumeister

1949 Essen

Egon Vietta, “Monte Cassino” (mystery play)

1950 Stuttgart

Otto-Erich Schilling, “In scribo satanis” (In the Devil’s Writings) (ballet)

1952 Darmstadt

Jean Giraudoux, “Judith” (drama)

1952 Wuppertal

Egon Vietta, “Die drei Masken” (The Three Masks) (drama)

1953 Darmstadt

Max Komerell, “Kasperlespiele für grosse Leute” (Punch and Judy Show for Grown Ups) (drama)