I cordially congratulate you on Frankfurt. It is even with special personal satisfaction since I intensely promoted you for other positions, but never got through … I very much regret that we will lose you in Stuttgart. Also, teaching is no unfettered bliss.“

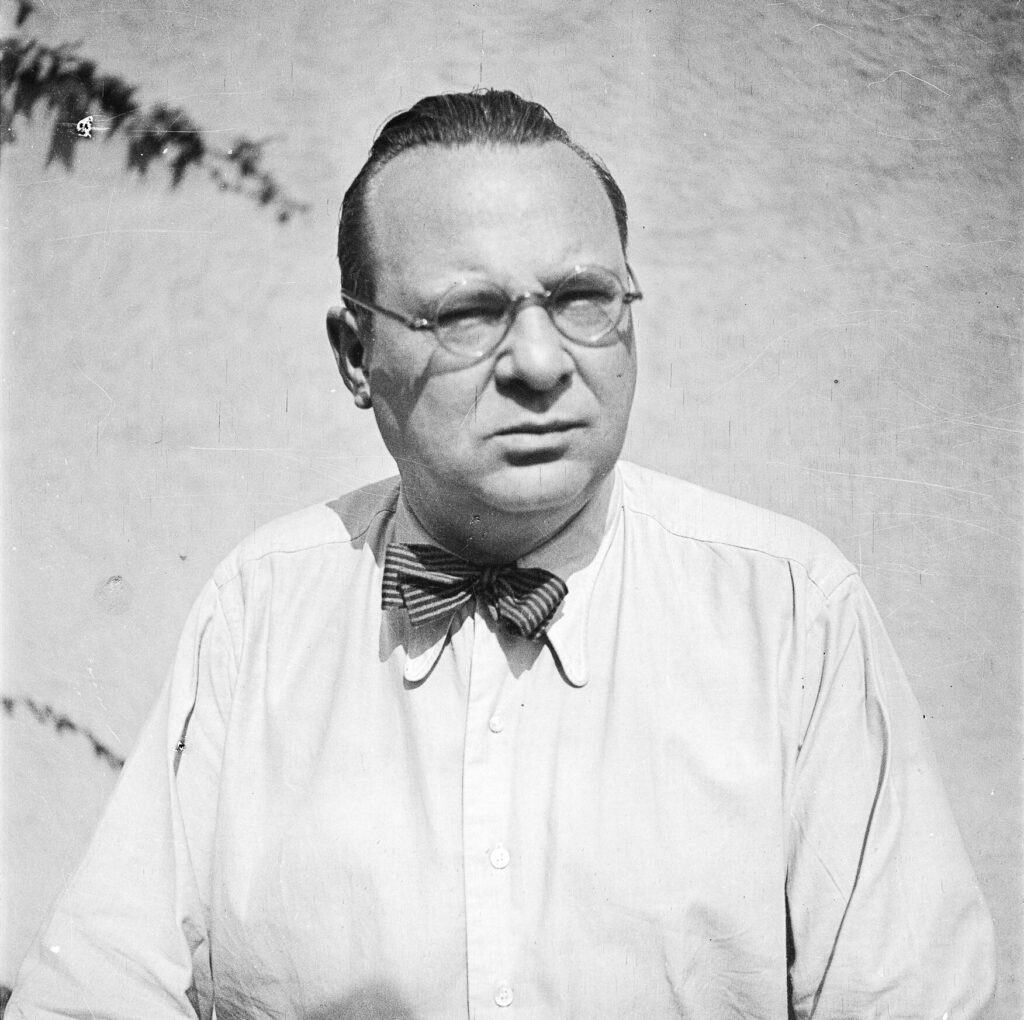

Thus wrote Adolf Hölzel to his former student Willi Baumeister at the end of 1927 after the latter had accepted a teaching position at the Municipal School of Applied Arts (Städelschule) in Frankfurt am Main in November.

This was preceded by a number of important exhibitions during the twenties in Paris, Berlin, Mannheim, and other cities and after he had declined a teaching position in Breslau in 1927. Friendships with important avant-gardists such as Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger or Amedée Ozenfant had been forged. In 1929 he even turned down an offer from the Bauhaus in Dessau.

The most crucial reason for his employment in Frankfurt, though, was Baumeister’s role as one of the exceptional typographers of the time. Since 1919 – along with artists such as Walter Dexel, László Moholy-Nagy, and Kurt Schwitters – he had considerably contributed to giving commercial art a new direction. The greatest success here was his varied participation at the Stuttgart Werkbund Exhibition “Die Wohnung” (The Dwelling) in 1927, whose atmosphere of a new beginning is evinced by the still extant Weissenhof Estate.

Tasks in Frankfurt

On April 1, 1928, Willi Baumeister took up his position at the [Municipal] School of Applied Arts in Frankfurt am Main. Also known as the Städel’sche School of Arts, the institute was one of the most important schools of progressive education of its time and in a very short time had become a center of new design. Baumeister did not teach the subject of painting, though, which Max Beckmann covered, but was hired as head of the class for commercial graphics and typography. Made professor in October 1928, he also took on the subjects of weaving and photography in 1930.

Art and Commercial Art

Baumeister by no means perceived it as a slight that he was not employed as a painter in Frankfurt. On the contrary: for him commercial graphics had such a high esteem that he even declined to mention painting on his letterhead of 1924. Since the turn of the century, uniting art and everyday life, removing the division between the applied and fine arts, was the declared goal of many painters, graphic artists, and architects, and, among other things, led to the foundation of the German Werkbund (1907) and the Bauhaus (1919).

This notion of synthesis was thus one of the fundamental bases and contents of Baumeister’s classes. The former director of the school, Dr. Fritz Wichert, explained the appointment at the end of 1927, noting that Baumeister belonged

… to a tendency within art that above all set itself the task of clarity and the strictest regularity of picture appearance. This attitude also corresponds with the aims of our school insofar as it brings itself into unison with the endeavors of modern architecture in the best fashion.“

Baumeister as art politicians in the center of the building industry

In addition to Stuttgart, Frankfurt was a center for current events when it came to modern town planning in Germany. Since 1925, Ernst May (1886–1970) had been City Master Builder and initiated among other things, the large-scale housing program, “Neues Frankfurt” (New Frankfurt ), with the participation of many progressive architects and for which May emphasized the central importance of all arts to help solve the social question. Thus, he and Baumeister – who were about the same age – worked hand in hand from different sides on realizing a societal consensus.

Consequently, Baumeister’s employment is to be understood not only in artistic, but also in political terms. May and Wichert saw Baumeister’s role in training a generation of commercial artists who knew how to approach the social phenomena of democratic Germany – a challenge to which Baumeister himself undoubtedly felt a call and for which he was also prepared.

Accordingly, besides his teaching activity, beginning in 1930 Willi Baumeister was also responsible for the design of the magazine “das neue frankfurt” (The New Frankfurt, est. 1928), one of the most important journals for the cultural redesigning of the state.

Teaching content

In 1929 Baumeister outlined the content of his teaching, whereby the introduction of photography must be seen as anticipatory:

- General training in the artistic handling of the two-dimensional surface. Elementary compositions with black and white, color, line, writing, figure, photograph. — Nude drawing. — Designs for the entire field of advertising, considering the methods of reproduction.

- Technical training in [type]setting, printing, woodcut, and linocut.

- The bookbinding workshop teaches technical training in all branches of this craft.

- Complementary instruction in the subject of advertising, the study of materials, color theory, history of art.

- The addition of a photography workshop is planned.

- Evening classes for print-shop assistants with instruction in typesetting, letterpress, wood- and linocut printing.

Aside from his remarks on typography, only few of Baumeister’s own assessments from those years have survived – in contrast to his teaching activity after 1945. Director Fritz Wichert, however, comments on this, too: “Professor Baumeister attempts to teach his students … the application of general laws of the planar surface and, through the strictest demands regarding color and figurative composition, to protect them from the prevailing neglect. … Everything that takes place in it [his class], is aimed at countering the slippage in this field of design into the vulgar and artlessness through refinement and mastery.”

This evaluation largely corresponded to the appraisals of the Frankfurt press and art criticism.

It is also interesting to see how former students experienced being instructed by Willi Baumeister. His student Marta Hoepffner remarked on this subject after 1945 in a commentary about her studies at the Frankfurt art school.

… no unfettered bliss

Baumeister’s class for commercial art and typography was among the best attended at the school. Between 1928 and 1933 he supervised an average of 27 students. Thus Adolf Hölzel seems to have been right – Willi Baumeister wrote to Oskar Schlemmer in 1932:

In the morning I am continually burdened with 25 students, reviewing, also school-like supervision about arriving punctually, admonishing unexcused truancies, reminding, scolding, a hideous drill-sergeant job. In addition, the very complicated workshops, large composing room, photo, spraying, printing, designing diplomas for the city, supervising printing, being responsible…. On two afternoons [I give] ongoing instruction for beginners and fashion class. The other afternoons remain for me to work? or incidentally paint, as one can call it. In the evening at home I sometimes pull myself together to make pencil drawings. My drawings, especially the new ones, are the best that I have made up to now. … Should I ever be relieved of this torture, I will be well-trained, like the runner who for training runs with 10-pound weights in order to one day discard them for the final sprint.“

Furthermore, it cannot be overlooked that Wichert clearly had increasing difficulties accepting an abstract artist alongside the figurative post-expressionist Max Beckmann, which additionally burdened Baumeister’s position. Moreover, beginning in 1929, parts of the Frankfurt press also frequently polemicized against Baumeister.

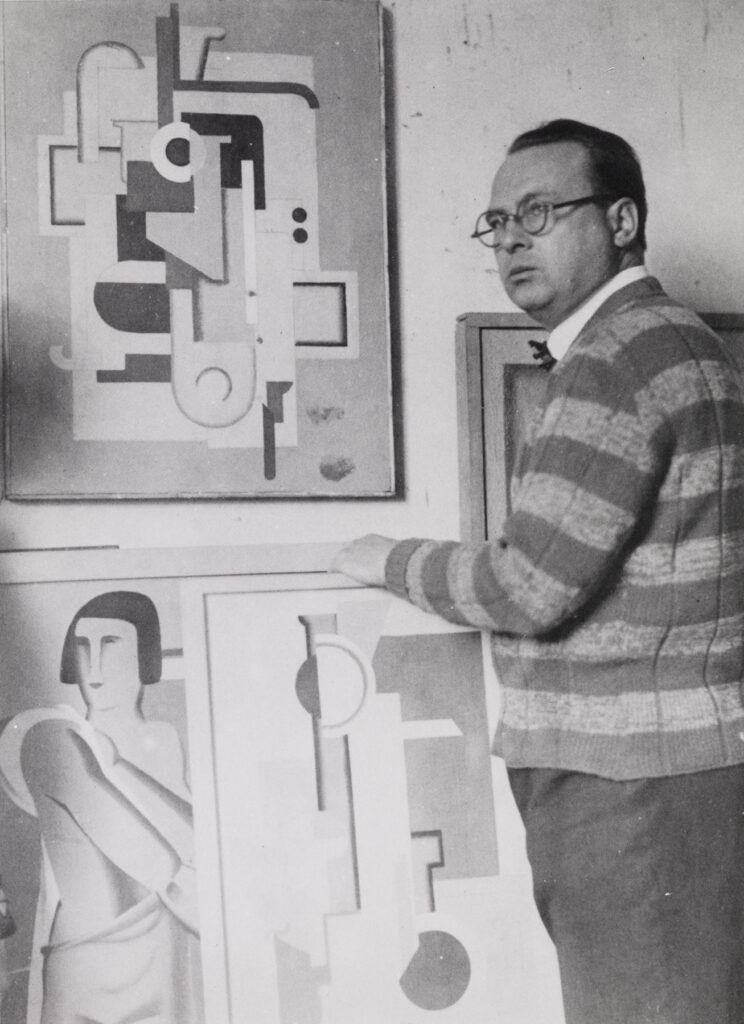

In light of the workload, the number of paintings in these years decreased somewhat, while the drawings increased. But Baumeister always took time for new picture ideas, as the Studio Pictures around 1932 reveal. However, we also know that he retrospectively rejected many works from around 1930 because he later saw some compositions as undesirable developments.

The abrupt end in 1933

After Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933, the events somersaulted, and not only for Willi Baumeister. They by no means came as a surprise, though, as nationalist (völkisch) tendencies had repeatedly surfaced in the culture scene since the 1920s. On February 13, 1933 the NSDAP assumed control of the Frankfurt city government, a few days later the (Nazi-party newspaper) “Frankfurter Volksblatt” incited hatred against Baumeister, and at the end of March Fritz Wichert was put on leave.

On March 31, Baumeister’s immediate termination followed in writing, but without further explanation via the new director, Karl B. Berthold: “I inform you that I renounce your further teaching activity at the School of Applied Arts. … [I] request … you refrain from any official activity and to evacuate your previous working space by April 8th.”

Willi Baumeister subsequently wrote in his diary: “According to the written communication from the new director Berthold, he “renounces” my further teaching activity. Therewith the “Frankfurt” chapter closes. … I was never politically active. (Should I undertake something against the dismissal? No. -) It is aimed against my “Bolshevist” art, which has been created out of spiritual freedom. What can there be that is Bolshevist about it? A great deal is characterized as “Bolsh. & Jewish.” What is not immediately understood by inferiors should now be strangulated?”

On April 7, 1933 Baumeister drove back to Stuttgart for good. The fate of dismissal was shared by many, including Paul Klee, Otto Dix, Ewald Mataré, Karl Hofer, Max Beckmann, and Baumeister’s friend Oskar Schlemmer. He remained in Germany, though, and by no means gave into resignation. His creative energy remained just as unbroken as his attitude of rejection toward the new regime.

Even though the doors in Germany only reopened for Willi Baumeister in the summer in 1945, these years during the Second World War would result in very important work groups (see the work phases 1936–1939 and 1940–1945.) Just a few months after the war’s end, Baumeister’s biography as an instructor continued with a new professorship in Stuttgart.

Contributing to the history of the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Art, Wolfgang Kermer’s book “Der schöpferische Winkel. Willi Baumeisters pädagogische Tätigkeit” (The Creative Angle: Willi Baumeister’s Pedagogical Activity) appeared in 1992, and treats the years at the Frankfurter Art School at length (see Literature).