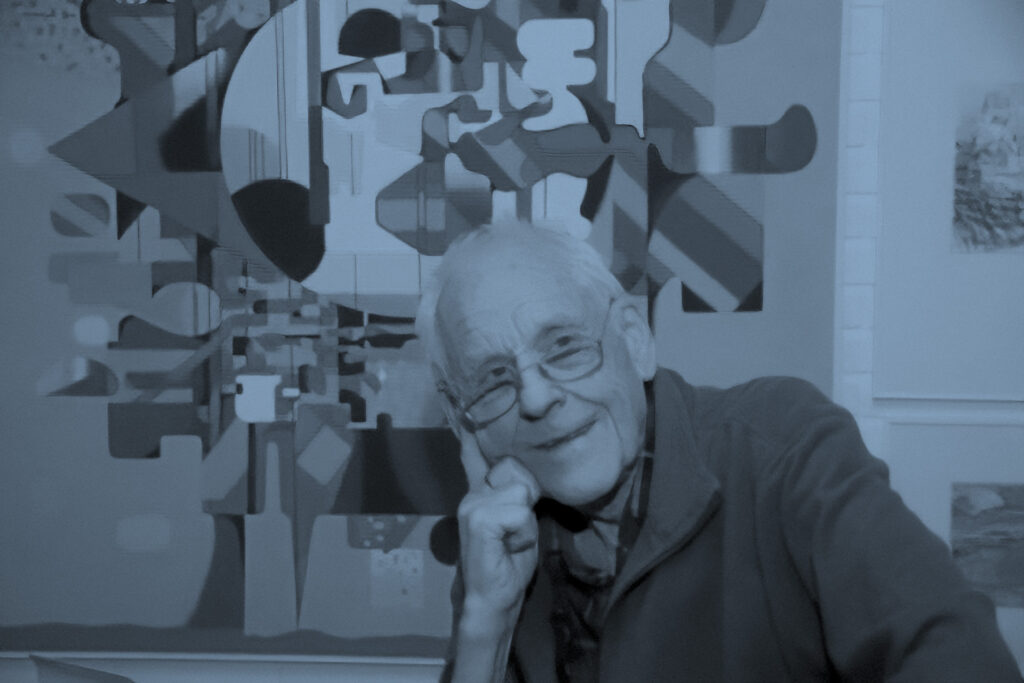

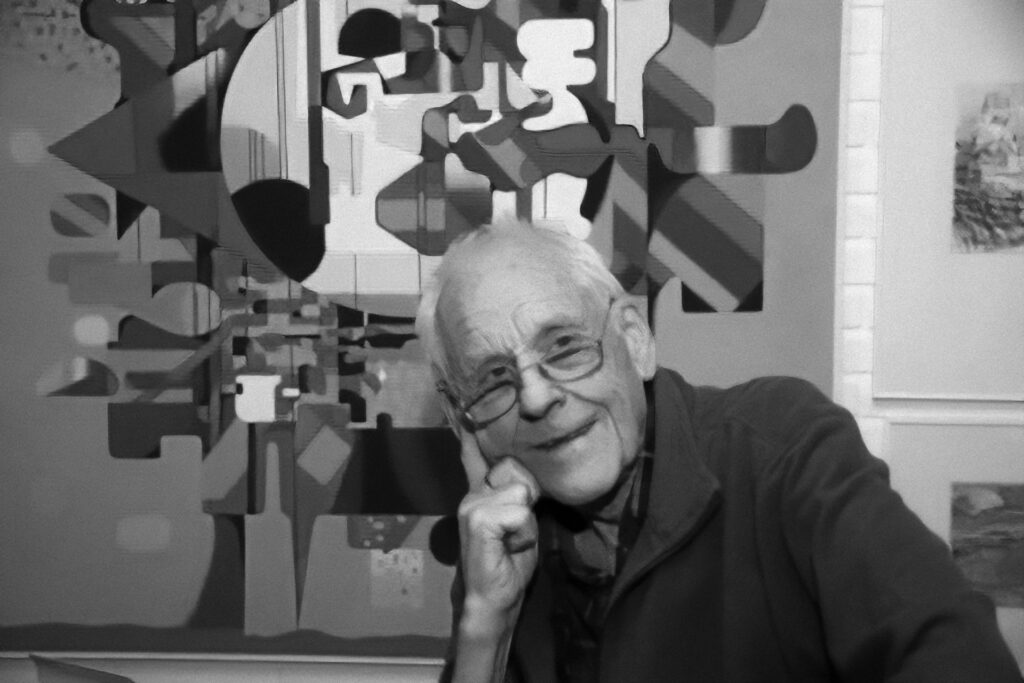

Gerhard Uhlig (1924–2015) attended Baumeister’s class from 1949 to 1953. In 1953 he became an art educator, and in 1969 the principal and deputy for art education in Münster.

During my art studies (art education, teaching position for grammar school) there were two teachers who particularly influenced my thinking in terms of artistic activity: J. Hegenbarth and W. Baumeister. Both were workers, detested artist affectations.

For Baumeister working meant the intensive, plain engagement with the objects through which picture information is presented/communicated, bound to an ordered, consistent work schedule, oriented toward a length of time, like that which applies to every other working person. Baumeister would become annoyed when a student was lax with work time, and he was not afraid to make that person aware of his disapproval.

Signatures on his students’ pictures or work sheets were undesired. Signatures were a sign of something finished, completed, of something that ruled out corrections. Those, Baumeister believed, who no longer needed teaching could sign; he needed to know that the signature is a mark of quality for the viewer. Those who were still in training and who signed [their works] lacked adequate insight into their performance level. Practicing needed to stand in the foreground, not the finished picture. With this attitude Baumeister sharpened our self-critique and sense of responsibility toward the viewer/consumer.

The strictness of Baumeister’s work discipline was coupled with tolerance and warm-heartedness.

Representational works could also be presented for reviewing, no one was slighted for that, in contrast to the conduct of a few other instructors teaching then, for whom Baumeister’s teaching was the seduction of youth and his students a red flag.

The discrepancy between Baumeister and these lecturers was obvious. Baumeister was shunned. I never saw him with them in the cafeteria, also not on other occasions. Whenever he had his meals in the cafeteria, he always sat at our table. He shared his food with those who had to live frugally. Even the bread and butter that his daughter occasionally brought to the academy he did not eat alone.

On Sundays, in the morning, those who were interested in his pictures in whatever form could visit him, whether as a possible buyer or just as a viewer. Visitors came from all over the world, from European countries and beyond. Despite the generosity with which Baumeister treated these matinees, they seemed an obligatory exercise to me. Often enough the visitors expected interpretations of the pictures that corresponded to their expectations; Baumeister did not care for this much. At these matinées he relatively often left the artistic care of the visitors to me. For me that was a mark of distinction.

Baumeister’s teaching accompanied me on my career path, not in a reproductive sense, but as a continuation. It had an effect on my own pictorial artistic work, especially and first of all, on my didactic task as art educator at the grammar school, then as principal of the school faculty in Munster with a field of activity that extended across entire Westphalia, and as director of events for further education (for grammar-school art teachers) of this administrative body.

If I wished to list principles that grew out of Baumeister’s teaching, I would name the following:

- Teaching art requires objectivity. It has to endeavor to make the transmission from the artistic object to the viewer/interpreter as free of interruptions as possible.

- First then can perception (under perception I understand the reception and further transmission of a sensory stimulation to the central organ [brain], observations, and reflections first begin there), observations, and reflections join into a sensible union and trigger practical action.

- Sensation precedes reflection; reflection is not possible without perception.

- The training of the senses is an essential condition of and to be equated with the training of reflection.

- Where the training of the senses is neglected, more theoretically acquired sensory data must inevitably be reflected. This results in a stagnation of creativity; creativity conditions new forms of perception and observation.

- On the basis of its broad, purpose-free range of freedom, art offers many new forms of sensation and perception. It promotes the sensibility of particular areas of perception and expands humans’ reception and processing abilities. In this the aesthetic component is the mediator by which can be perceived at all. Where it is made banal or repressed, a door or gate is opened to manipulations.

- The aesthetic component has a high sociopolitical and educational value.

For the art teacher the teaching goal is not the pictures, but expanding the abilities of those learning so that they act appropriately in their environs and thus toward the picture/design situation. The resulting picture, also the mental picture, serves as the check instrument for the teacher. The exercise is given priority because it also demonstrates better than the completed picture how far the student has achieved a learning success.

(From a letter to Wolfgang Kermer, dated April 22, 1986, quoted from Kermer 1992, p. 182 f.)