Klaus Erler (1926–died) attended Baumeister’s class from 1947 to 1948. From 1958 to 1985 he was a graphic artist in various advertising agencies. He was also active as an independent painter.

How I came to Baumeister: in 1946, I first began to study architecture in Stuttgart. Due to the widespread destruction around us, my idealism, a considerable skill in drawing, and a creative imagination were the mainsprings that lead to this decision. But it soon turned out that the art history lectures, especially those on modern art, began to grab my interest more strongly than the lectures and exercises on building. Since I had always painted (chiefly in watercolor), I felt an ever-stronger artistic impulse from the art lectures, especially from Prof. Hans Hildebrandt, so that in January 1947 I decided to switch to the art academy.

I became acquainted with some of Baumeister’s students (including Gerdi Dittrich and Jaina Schlemmer) who encouraged me to request admittance to his class. The students simply took me along to a reviewing class, where I tacked my first abstract watercolor to the wall with the other students’ works. I called it “le rouge et le bleu (the red and the blue)”, because it contained lively red color bands that were penetrated by blue pointy crystal shapes, made a bit in imitation of Franz Marc, whom I glowingly admired at the time. I do not recall Baumeister’s exact comments on this experiment; he probably found it too expressionist. But he must have granted me some goodwill, since after he asked Gerdi Dittrich privately what she thought of me and whether he should take me on (and she positively encouraged him), I was accepted. At least that is what Gerdi Dittrich told me later.

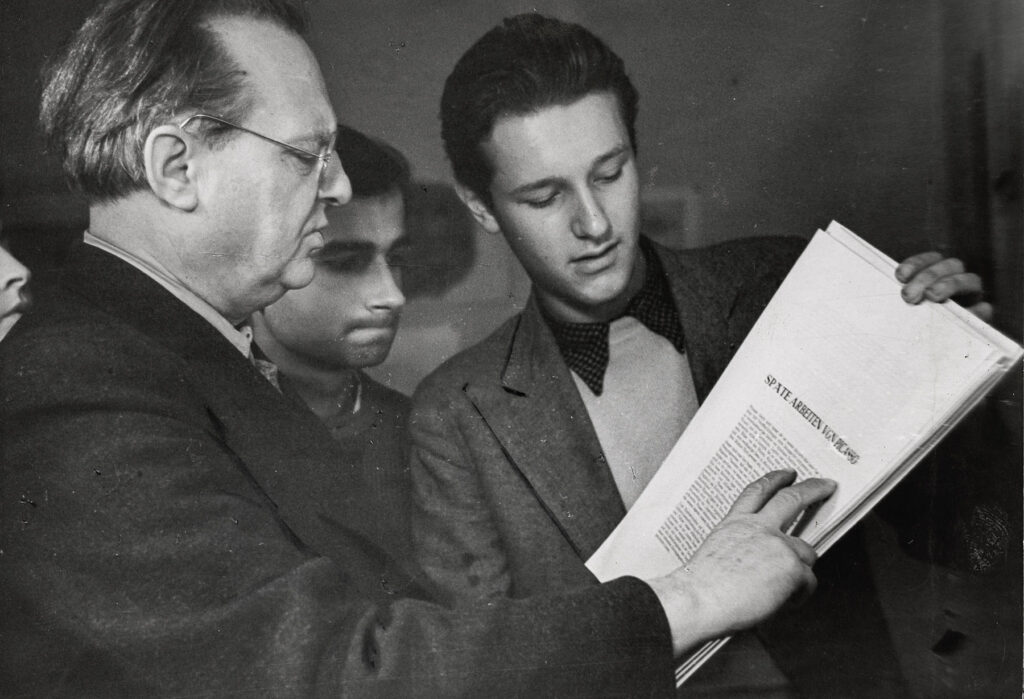

In the beginning there was a thoroughly private tone in all these strivings and all these decisions, a wonderful atmosphere of giving and taking, a warm human closeness that also included personal visits with Baumeister in his familial circle. As such I could also participate in the reviewing classes without being an officially enrolled student. But I found Baumeister’s demonstration with prints by other modern masters almost shockingly revolutionary; for instance, a Mondrian picture that was shown and discussed ignited profound discussions, whereby Baumeister also praised Mondrian as a modern great artist and explained his achievements to us. This discussion went even further into the private sphere, by which Baumeister more by chance, was also present and again confirmed his point of view to Mondrian’s advantage.

My enrollment eventually took place in winter semester 1947–48, following an internship as a house painter, which was required by the Academy Direction and which I completed in summer ’47.

Now an intense period of painting, research, practicing, and designing began, and always with regard to Baumeister’s judgment and the now greater number of fellow students in the class. When I once spoke to the class on the “artistic state” that it was defined by an “energy gradient” in the sense of modern physics, I was laughed at. But Baumeister, who put only a slight damper on my scientifically inspired élan, basically justified my point of view… It felt good to be taken seriously on this point by a master.

Still, in the class I was often teased a bit with regard to my “Bullet-Flash” paintings and affectionately mocked with the question of what my “energy gradient” was up to. On another occasion, though, Baumeister himself also brought up an apt example of the peculiar nature of the artistic state. When he was asked when it was that he could best paint or put himself into the “artistic state”, he replied that for him it led to a creative impulse when, for instance, he was looking forward to a theater performance or something else interesting and then the event would for some reason not take place. If he was disappointed and sat down at the easel in this state, painting would go especially well.

He once criticized a student (…) who presented heavy, paint-encrusted pictures in a thick impasto on canvas as too extravagant in paint consumption and intention (whereby he consciously ignored the slightly surreal horse motifs). In contrast, he praised my casually tacked up sign-like studies that were painted in India ink on thin white and yellow wastepaper. [He found] they were more effective even if only for the economical use of materials. But pictorial asceticism was not to be taken too far. Constructivist compositions, such as those by Max Bill, he generally found “too thin”, as he once said to me…

(From a letter to Wolfgang Kermer dated April 16, 1986; quoted from Kermer 1992, p. 186 ff. )