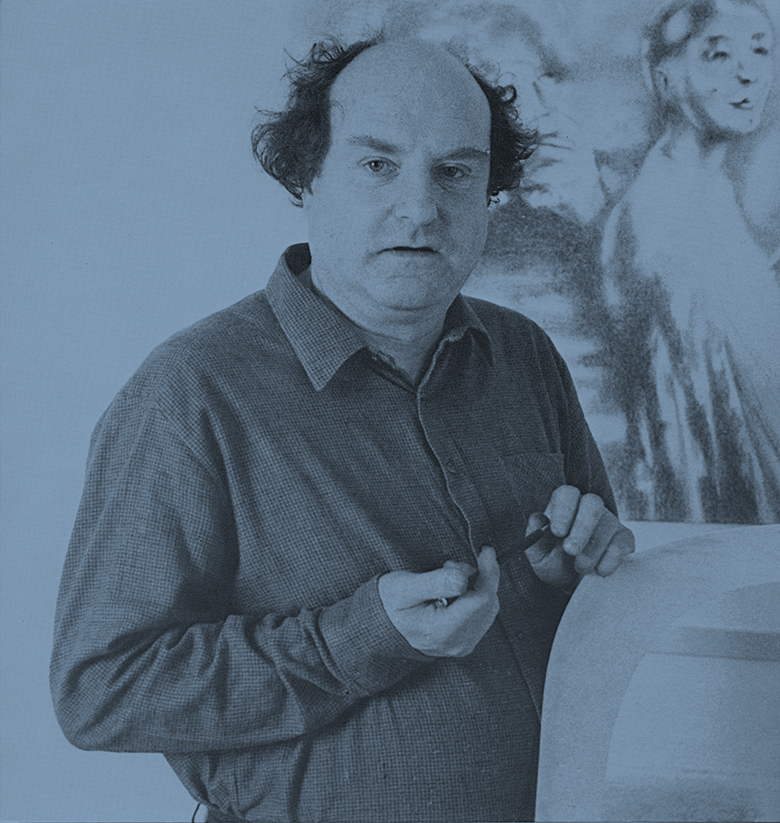

Peter Grau (1928–2016) attended Baumeister’s class from 1946 to 1953. From 1968 to 1994 he was professor for general art training at the Stuttgart Academy.

Baumeister’s first generation of students 46–47, set up in the old building in the rooms of the what was then to become the Dreyer class, was very lively, open, and comradely, even if there were harsh discussions now and then. In Baumeister I came to know a teacher who – always aware of his path and referring us to Cézanne and Picasso – definitely tolerated when works deriving from other trends were produced in his class. His staunch belief was that from Giotto up to Cézanne was the representational epoch, but from Cézanne on was the nonrepresentational one. That, however, did not keep him from allowing exceptions to this rule and affirming them…

I owe to him the sharpening of my eye for the elements of a picture’s composition, knowledge of surface tensions that even can be applied to the design of spatial depth. I own to him the sharpening of my eye for the soloists – (the dominating forms) – in a picture’s structure and its size (dimensions), and placement in the picture space. To him and the ancient Chinese I owe the insight that the soloist acts most strongly when it appears where it is not expected, that small shifts in a picture composition represent no disadvantage in the face of the laws of logical interconnection, but rather, that these mistakes can first bring the picture to life. (Negative example: the current computer art). His repudiation of symmetrical compositions is to be explained with his extremely fine sense for the free play of energies. The art of proceeding with the sketching of a picture – (“…everything totally black from all the strokes…”) – he criticized in his teacher Hölzel as too restricting and no longer allowing for changes.

I am also indebted to Baumeister for the insight into the essence of color, which helps me a great deal on my completely different path. Even after the beginning of my violin studies at the State College for Music in Stuttgart, I did not stray far from Baumeister and the Academy. Music was the second track, but I was and remain a graphic artist.“

Peter Grau

(Excerpt from an essay in “Hommage à Baumeister — Freunde erinnern sich an ihren Lehrer” (“Homage to Baumeister — Friends Remember Their Teacher”). Exhibition catalog Galerie Schlichtenmaier, Grafenau Schloss Dätzingen 1989, p. 53 ff.)

I had a unique experience during one of the many private visits I paid him in his home and neighboring studio house. Baumeister was apparently very sensitive to changes in the weather, as low [barometric] pressure put him in a sad mood. When it drizzled he spoke about things that one otherwise did not hear about from him. In short, he had just completed an oil painting, a precursor to the Montaru series that presented an unusually heavy, black block in the lower right corner. I noticed it because Baumeister otherwise composed with a sleepwalker-sure sense for balance. To my query he explained that this picture was a battle against himself, a thorn in the side, and a great agony. These words – correctly understood – are completely monstrous and signify a rebellion against laws that are stronger than the human. I also do not know whether he left the picture as it was, as I have not seen it since then.