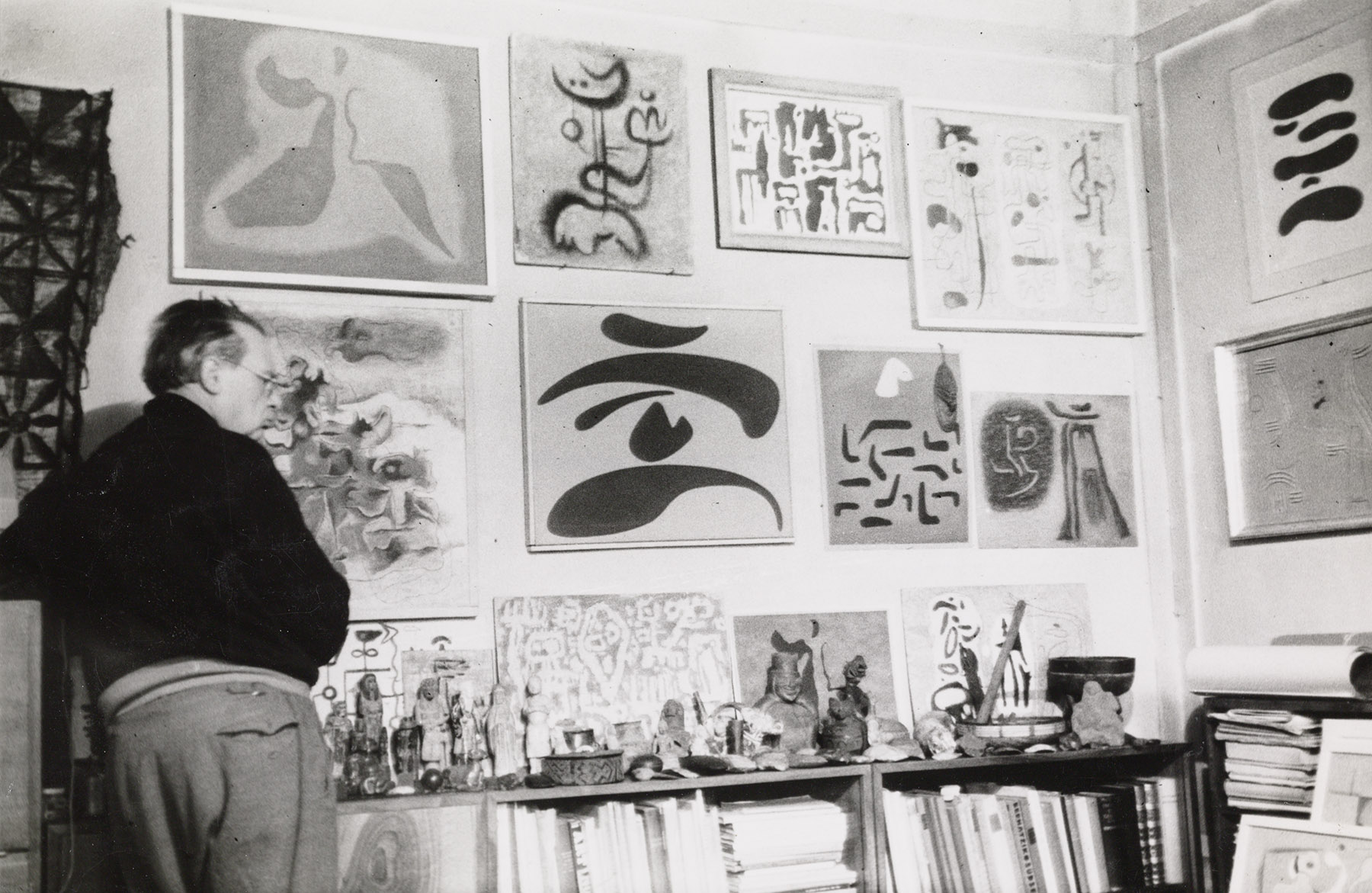

Willi Baumeister’s collection of ancient and nonwestern material culture contains around 250 objects. Astonishing is the collection’s breadth in terms of cultural regions and time periods, but also in light of its figures, masks, and other artifacts’ variety of functional and handicraft.

The different parts of the collection were a source of inspiration for him, from which he made his art. He stressed that the old myths of the entire Near East take on a particular role in which the primordial energies of life are given expression that contemporary humans can understand.

Rescued from Destruction

Baumeister began the collection at the end of the 1920s and completed it between 1940 and 1943. This unique evidence of an artist’s collection fortunately survived the wartime, because Baumeister gradually took the objects in suitcases from Stuttgart to Urach, where he fled from bombed-out Stuttgart in 1943.

Africa Collection

The beginning of Baumeister’s great interest in nonwestern art cannot be precisely dated. Even so, it is conceivable that he came into contact with African art beginning in 1924, when he met the French artist-colleagues Le Corbusier, Amedée Ozenfant, and Fernand Léger in Paris. Especially in the French art magazines Cahier d’Art and documents illustrations of African art appeared. Margarete Baumeister, the artist’s wife, discovered a Senufo Mask from the Côte d’Ivoire in the basement of the Galerie d’Art Contemporain. Baumeister had his first solo exhibition in Paris in this gallery in 1927.

From this time on, he acquired African sculptures, masks, functional objects, wooden and woven bowls from various African cultures. The growth form or tree trunk could still be seen in the sculptures, aspects that interested Baumeister.

The coloring of the caryatid figure with a vessel on her head comes close to Baumeister’s paintings, which he called in the African style. On June 16, 1943 Baumeister wrote to Dieter Keller: “I am now painting black on an almost pure white ground […] with rough, frayed strokes […]”. Already the painting Drumbeat of 1942 showed this manner of painting. His interest also extended to the painting of an antelope-skin covered wooden box from Cameroon with traditional, geometric stylized motifs, in which redwood paste used for the body painting was kept.

Stone Age Collection

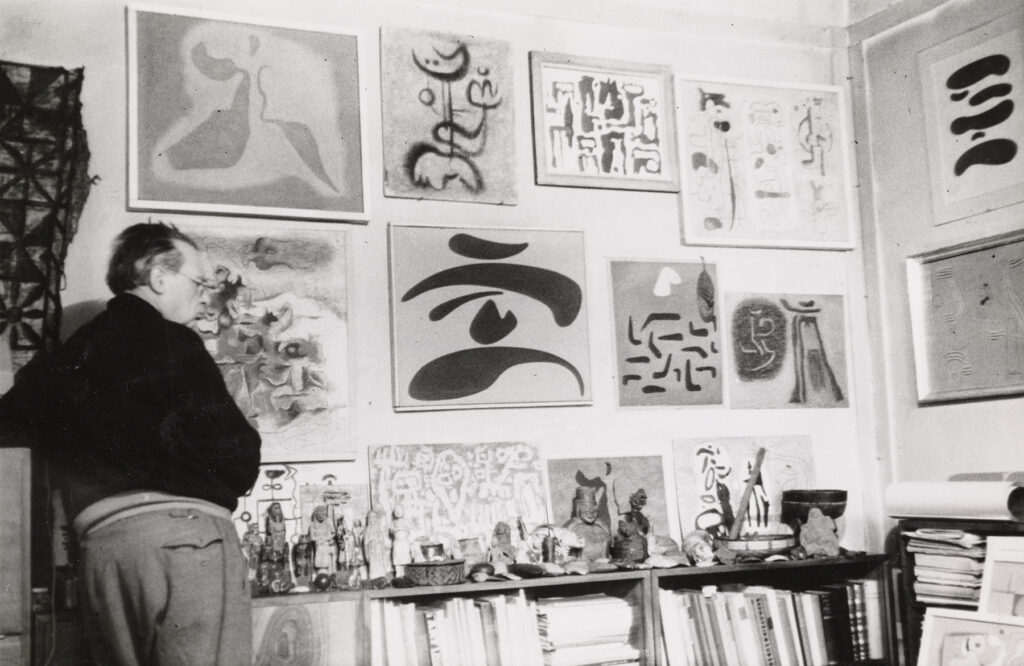

Baumeister was also especially interested in early ancient small sculptures from the Mediterranean and in Egyptian ushabti (shabtis in English). His collection includes fossils, prehistoric vessels, stone axes. While Baumeister taught as a professor at the Municipal School of Applied Arts (Städelschule) in Frankfurt, he took the opportunity to attend lectures by Swiss cultural historian Hans Mühlestein. Mühlestein held seminars on the primeval history and prehistory of humanity and, in turn, was an admirer of Willi Baumeister’s art. At this time Baumeister increasingly began to collect stone tools from the Paleolithic to Neolithic periods (about 15,000 to 20,000 years old) of various origin.

He patinated a series of casts in stone and earth tones such as, for instance, the mammoth engravings and small sculptures from the Vogelherd (near Stetten in the Swabian Alb), which are among the oldest discoveries of prehistoric works of art. In Baumeister’s view, the origins of art were to be found in the early Stone Age. He investigated the painting techniques of stone-age rock and cave painters and discovered that these paintings needed no binding agents. The ornaments and scratch and line figures of subsequent cultures interested the painter. He allowed himself to be partially inspired by them in his own works as, for instance, in the Stripe Composition on Purple or the Figural Ideogram, both of 1945.

Motivated by the ethnologist Leo Frobenius in Frankfurt, founder of the Africa Archive, whose chief task was the compiling of ethnologic and archaeological objects, Baumeister also collected in this manner. Through viewing illustrations in books of prehistoric rock pictures such as the Valltorta Gorge in eastern Spain, Baumeister gained inspiration for his art. The rock pictures of Fezzan in Libya that Frobenius had photographed in 1932, also had an effect on his art. On August 2, 1934 Baumeister wrote in his diary:

I want to increasingly leave the composition of machine and wall pictures in favor of direct expression through the hieroglyphs (human), in the manner of the runner, the sign. My sympathy for stone tools and also for replicas of nature of the organic or inorganic kind, likewise my penchant for cuneiform script and hieroglyphs, may indeed lie close to the ideograms[…].“

A connection to the “Ideograms”, “Flying”, and “Floating Forms” exists in the smoothly finished stone implements.

These forms float, without touching each other, but are strongly attracted to one another in the plane. I initially intended them to be completely abstract, but further into the process saw figures in them, naturally frontal ones.“

Mesopotamia and the Near Orient Collection

Baumeister was especially attached to the ancient Orient. The pieces of his collection meant a great deal to him and his interest in this cultural region was immense, especially in the thirties when he enthusiastically read the field reports of archeologist C. Leonard Woolley, such as “Ur und die Sintflut” (Ur and the Flood, 1930) and “Vor 5000 Jahren” (5000 Years Ago, ca. 1930). The harp motif in some of his works from around 1945 is derived from the “lyres of Ur”.

The incised figurative depictions on cylinder and stamp seals and the uniformly structured surfaces of the small ancient Assyrian cuneiform-script tablets made of clay in Baumeister’s collection inspired him to make paintings such as “Structural” of 1942 or “Remnants of Memory” of 1944.

Egypt and Greece Collection

Baumeister also loved the art of the ancient Egyptians. He estimated this art to be – as he put it – direct painting that is built up of elementary forms as elements of the expression. Some wooden Shabits and two bronze Osiris figures appear in his collection.

Willi Baumeister’s interest was also drawn to a small mummie casing, whose typical non-perspectival representation particularly enthralled him: the head in profile, the eye frontal, the shoulders frontal, belt and buttocks from the side […]. (Baumeister, 1947)

Beginning in 1940, Baumeister collected terracotta statuettes from the Aegean culture, Mykonos, and Boeotia. Ancient Greece is represented in the collection by several of these early archaic small works of art. Baumeister showed great interest in the Cycladic idols of which he acquired plaster casts that he patinated in gradated earth tones. In 1940 Baumeister wrote to Heinz Rasch that for him “sculptures from the Greek island art were probably the strongest stimulus to his own actions and work.”

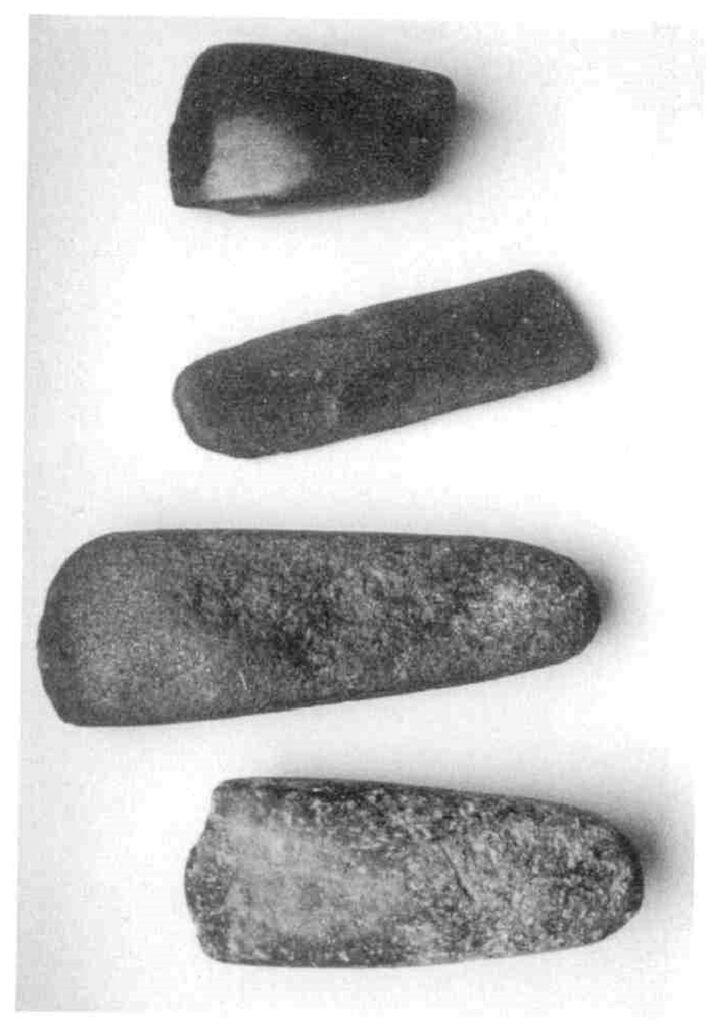

East Asia Collection

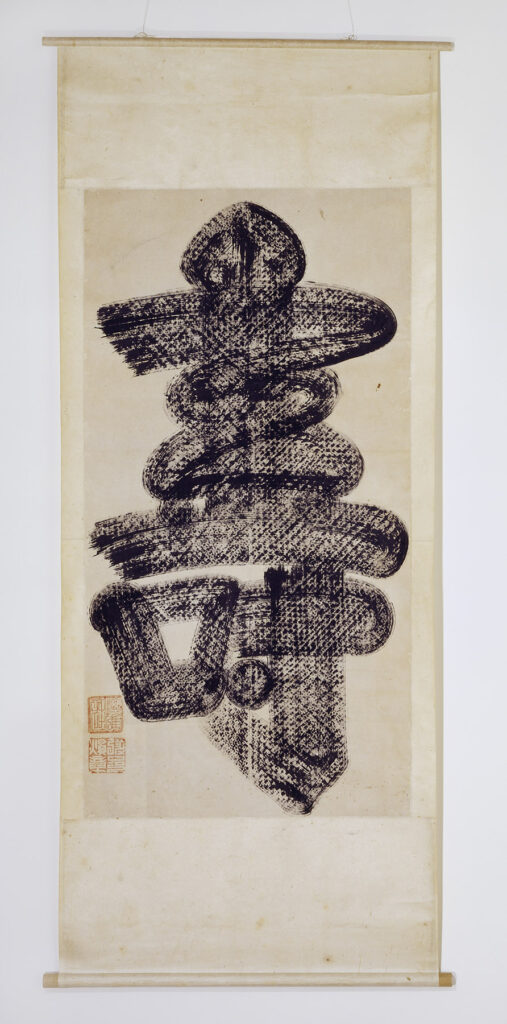

Die Weisheit des Ostens, die fernöstliche Philosophie sowie die Kunst Ostasiens sprachen den Künstler besonders an. Seine Sammlung enthält 46 Objekte asiatischer Herkunft, darunter auch eine kleine Kollektion chinesischer und japanischer Holzschnitte. Das wichtigste Objekt darunter war für ihn das Rollbild in Tusche auf Papier aus dem 19. Jahrhundert mit dem Schriftzeichen “shou” (für Langes Leben), das er 1941 von Dr. Kurt Herberts als Geschenk erhalten hatte.

During the war aumeister also began to explore Zen Buddhism, which greatly influenced his notion of the Unknown. The rubbings of gravestones from the Han period (206 BCE to 220) fascinated him so much that he also called a few of the pictures he produced the year he died, 1955, Han‑i out of sympathy for the Han epoch.

Precolumbian America Collection

Baumeister owned a few works of ancient American art from the Precolumbian period, Central America, and ancient Peruvian cultures. Many objects came from a time that preceded the Incan Empire. The sign-like quality is so pronounced, even in the mimicry of some figures, that we can understand Baumeister’s interest in this culture. He also collected ancient Peruvian weavings.

The statuary art of early high cultures found manifestation in numerous paintings, such as the Maya Wall of 1946 with its interlocking figures. There is even a direct correspondence to a pair of figures in the picture Aztec Couple of 1948. In a certain sense Willi Baumeister translated the style of the Aztec culture into his own – painterly – language.

Oceania Collection

One emphasis of the collection is the compilation of Oceanic objects that come from the Sepik region of New Guinea. Among other objects are also a heavy combat shield with a height of 1.4 meters (ca. 55 inches) and a slightly smaller ceremonial (dance) shield. The extraordinarily expressive ornamental and figural formal realm refers to the world of spirits and the cosmos – a thematic area that continually captivated Baumeister not only in the 1940s, but also over many decades while working on the “Unknown in Art”.

But Willi Baumeister was also interested in the coloration that, mostly earth-colored, was mixed from natural pigments. As such, blue and green occur only rarely in these objects. For him the 1.75-meter wide Polynesian tapa of cow-raffia cloth or ceremonial Malangan head sculpture from Papua New Guinea were examples of an uninhibited, civilization-remote art within a cultural area in which life and artistic processes formed a unity. Achieving this goal in the modern art of Europe was also a continual aim of Willi Baumeister.